Tackling the Perfect Problem

This article was first published on Pure Advantage, New Zealand’s leading green growth organisation.

____

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman, one of the world’s brightest minds, is very sorry about what he’s got to say: “I’m deeply pessimistic. I really see no path to success on climate change”. According to the guy who knows our own brains better than we do, and with a Nobel Prize to prove it, the threat of climate change is simply too “distant, abstract, and disputed”. Climate change “just doesn’t have the necessary characteristics for seriously mobilising public opinion”. Widely examined in academia, but seldom shout to the layman, climate change is not just a political problem, it’s a psychological one. In theoretical terms, it’s the perfect problem: climate change has no single identity, no single cause, no single solution, and no single enemy.

James Shaw (NZ’s Climate Change Minister), Jacinda Ardern (NZ’s Prime Minister), Daniel Kahneman (Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences)

Fortunately, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern already knows a thing or two about psychology; her powers of persuasion landing her the top job. The Jacinda effect has also promised a thing or two on climate change: A Zero Carbon Act, an independent ‘Climate Commission’, and most incisively, an “absolute commitment to climate change” — her emotionally persuasive “nuclear-free issue of our generation”.

So far, so good, it seems. Prosperous little New Zealand, after nine years of procrastination, now has a leader braced — and bold enough — to do something about the biggest economic, financial and environmental issue facing the world.

Granted, listening to the likes of Kahneman may be the last thing on Ardern’s agenda, but her speechwriters, her coalition ministers, and even her partner, might prevent future hassle by encouraging her to do just that. Bringing around the thousands of New Zealanders sceptical about our government’s soon-to-be “blimmin’ ambitious target” for net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 could depend on it. Paving the way for 2018’s political necessities to be more probable and less partisan will depend on it.

Climate change is distant. It’s also here.

There’s little doubt Barack Obama is one of our planet’s most renowned communicators. Yet when it came to communicating about climate change as U.S. President, he was like Kanye West at Glastonbury — he just didn’t get it. Future this, future generations, future that. It’s not that people don’t care about the future; it’s that they care more for the now. Much more. According to Kahneman, the Optimism Bias — our tendency if we’re smokers, say, to believe we’re less likely to contract lung cancer than other smokers — is but one of many time-preference biases that obstruct us from acting on future threats.

Goals for 2050 and future accountability are vital in 2018 legislation, but Ardern and co must invoke the now in 2018 communication. After all, it’s not a matter of waking up our future adults (the Young Nats even awoke this year), it’s about reminding New Zealand’s dyed-in-the-dairy farmers and the Old Nats that this is happening now, and we’re doing something about it, now.

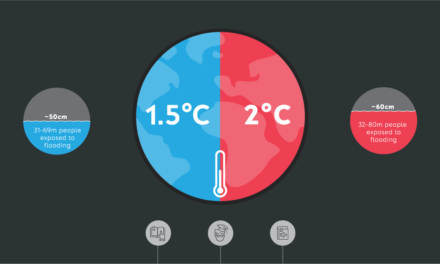

Since the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015, global temperatures have averaged 1°C above their pre-industrial average. Since 2016, atmospheric concentrations of CO2 have averaged over 400 parts per million for the first time in several million years. In 2016, over 23 million people were displaced by weather-related (and climate-change-exacerbated) disasters. Cyclone Winston — the strongest recorded tropical cyclone to make landfall in the Southern Hemisphere ever — devastated our pacific neighbour Fiji, killing 44 and costing the economy 20% of its annual GDP.

Closer to home, 2017 was foundational. Forget the election. The charity Trees That Count planted 8.5 million trees to start our afforestation ball rolling. In March, UK outfit Vivid Economics, commissioned by GLOBE-NZ, wrote a report (Net Zero in New Zealand) outlining scenarios to take us to the vanguard of climate-change policy globally — and to profit from doing so. In April, youth organisation Generation Zero launched its blueprint for the Zero Carbon Act (2018). In June, ‘Dairy Action’, a joint Dairy NZ and Fonterra partnership launched, reportedly committing to tackle climate change and simultaneously protect our waterways. Its integrated, ‘co-benefit’ approach dovetails with the work of the Biological Emissions Reference Group (BERG), a cross-industry (and former-National government) initiative which will present the evidence base for reducing our agricultural emissions. Its final report is due in a matter of weeks.

This year, by focusing on additional co-benefit approaches — for example, measures from McKinsey & Company’s recently published ‘Focussed acceleration’ strategy for cities or Paul Hawken’s book Drawdown — we can enjoy the psychological advantage of promoting tangible improvements alongside almost-hypothetical 2050 scenarios. I don’t know about you but improving our cities, our health and my ability to swim in rivers tugs at my emotions more than, say, “by 2040 it’s estimated Canterbury and Otago will be in drought about 20 percent of the year” (up from 10 percent a year today).

Climate Change is abstract. Let’s make it concrete.

After former World Bank Chief Economist Nicholas Stern completed his 600-page analysis of climate change in 2006, he spat out a single sentence: invest 1% of global GDP in the next 50 years to mitigate the worst effects of climate change, or don’t, and gear up to spend 5 to 20% of GDP on a changing climate — indefinitely.

Stern’s economically rational message sits particularly unsteadily with Kahneman’s findings. The trouble is people like to spend their money on things they get now, and things that are guaranteed; not on things they’ll get in a few years that, let’s face it, are mere abstractions in our stone-age-wired brains. Equally daunting to what psychologists call our ‘Discounted Utility’ (or ‘Present Bias’) is Kahneman’s insight that people tend to be prepared to take greater risks on potential losses than potential gains — especially if those losses lie in the future.

As psychologically inconvenient as it all is, tomorrow’s climate change does demand that we invest in the short-term to ensure the long-term. But there’s much more in it for us than that. For a start, individual costs needn’t be incurred if James Shaw and Ardern get the meta-right. The policy spur should be provided by a functioning carbon price-signal for all sectors, a cross-party supported Act that creates long-term predictability, a plan to offset our land-use emissions through afforestation and technology, a commitment to welcoming foreign innovation, and upgrading our “evidence base for low-emissions pathway planning”. Business will do a lot of the rest.

New Zealand companies know climate change is concrete because they’re already benefiting from doing something about it. Westpac Bank acknowledged as much in September when it handed over $50,000 to Ecoware, an eco-packaging company, and when it increased its lending to $10 billion by 2020 for New Zealand (and Australian) businesses tackling climate change. Matt Fordham and Shay Brazier knew climate change was concrete back in 2013 when they started their energy automation company, Evident, which takes intelligence to sustainability — in buildings and in cars. SolarCity continues to brace themselves for the inevitable soar of solar, most prominently through their removing of entry obstacles for their customers. And unlike 2011 — when their vision was a 100% solar New Zealand by 2020 — today’s plummeting international price of photovoltaics has their CEO Andy Booth talking sense again: “when it comes, it will happen very quickly”.

Climate Change seems disputed. Focus on the wins.

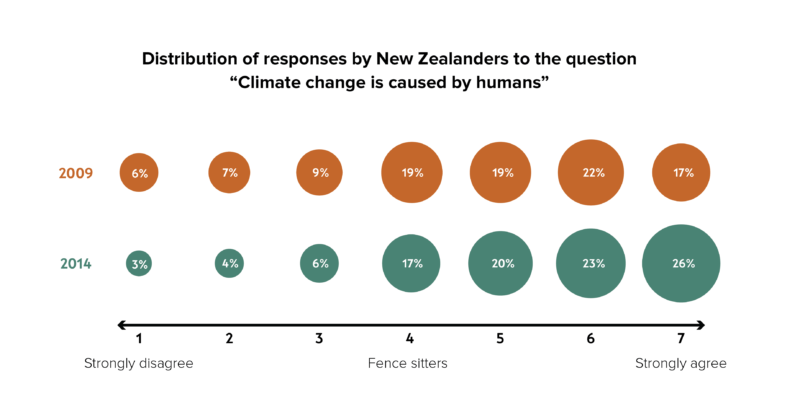

It’s true. Human-induced climate change remains disputed in New Zealand. A 2017 longitudinal study by Victoria University examined climate change ‘beliefs’ from 2009 to 2015. Despite the finding that climate change is becoming less disputed over time, the study couldn’t disguise the fact that climate change was still disputed: for example, only 69% of the 2014 respondents “agreed” that climate change was human-caused.

Created by John Lang from data at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174246.t001

Unsurprisingly, fringe denialist murmurings still enjoy a subterranean presence in New Zealand. Last year, a group of Waikato and Massey University professors presented a paper titled Doubt, Delay, and Discourse: Skeptics’ Strategies to Politicize Climate Change in an academic exposé of the dirty discursive tactics used by outfits such as the New Zealand Climate Science Coalition (NZCSC). Determining the longevity and effects of NZCSC (and others’) attempts to sow the seeds of doubt into New Zealanders’ minds remains incurably difficult to quantify, but one thing’s certain: policy action on climate change has continued to be delayed. Time may have blunted NZCSC’s vocal chords, but time is not on our side.

Building on the momentum of climate action globally — think Bloomberg, not Trump — the burgeoning business case for climate action offers opportunities to secure buy-in from our most sceptical. Irrespective of intentions, the doubtful can’t easily argue that our clean green image is not worth tens of millions a year to us or, for example, that diversifying our animal herd will not help future-proof our economy. Or, while we’re here, that investing in “no-regrets negative emissions technologies” such as afforestation will not help reduce uncertainties, bring about co-benefits and prove cost-effective.

Kahneman warns us that because climate change seems contested, “people with little time to investigate it will score it as a draw”. The challenge for our leaders is to show New Zealanders with little time that it’s an opportunity to win.

We’re Very Sorry Mr Kahneman

Sure, Daniel Kahneman’s got good reason to think climate change doesn’t have the necessary characteristics for seriously mobilising public opinion. But don’t you think he’s underestimating someone? New Zealand has always liked tackling its perfect problems. At the dawn of this century, Australian rugby legend John Eales caused us all sorts of headaches. He was nicknamed Nobody because of it.

Nobody’s perfect. Climate change doesn’t have to be.

Australian rugby legend John Eales, otherwise known as Nobody

Spot on – well done. In my view, part of the psychological problem is that endless economic growth has now become an article of religious faith. For the last 100 years, we’ve seen massive progress in poverty reduction, longevity, and material well-being. All leading to the promised land: the glossy-magazine lifestyle for all. How seductive. No wonder we assume it can go on unimpeded for ever. Endless progress is now a cargo-cult – the dominant faith of our time, especially among the science-illiterate.

Resource limitation issues (of which climate disruption is merely the most urgent) directly challenge this fantasy. Raising doubts invokes disbelief, derision, anger. You might as well tell an ISIS fanatic that Allah does not exist.

Hi Graham, completely side with this perspective but the facts necessitate we must run parallel campaigns: propel the climate curve downwards by acting within the system we’re all part of, while at the same time, advance — from inside and out — the moral and business necessity that is best summarised by living inside Raworth’s Doughnut.

I recommend her book, but it’s of course how we action it that needs all of our attention. I reviewed it recently https://e-nvironmentalist.com/review-doughnut-economics/

As a relevant aside, the psychology of climate change remains the most fascinating (and depressing) aspect of the issue for me.