Solitude

Michael Harris

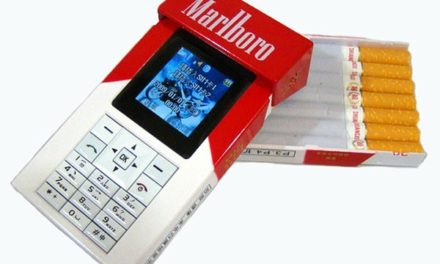

In one of the most revealing studies of the last decade, a team of University of Virginia psychologists set out to see how good undergraduates were at entertaining themselves. They left students alone in a room and asked them to ponder over whatever was on their mind for fifteen minutes. But – and here’s the crux – if students felt starved of stimulation, they could shock themselves. And zap themselves they did, with over half of the students choosing electricity over solitude.

Reading this for the first time, I couldn’t help but smirk a little smugly at these easily bored Millennials. I would never succumb to such desperation! But once my silent gloating settled, I realised I had been on my smartphone for the last hour or so. And apart from the occasional run, I couldn’t recall the last time I’d been separated from my digital companion. Was I just as bad as these students? Had I become afraid of being alone with my thoughts?

We all have, according to author Michael Harris, whose book Solitude: In Pursuit of a Singular Life seeks to find out why. And it’s something every introvert should be interested in.

A book for introverts

Harris is a Canadian journalist who is somewhat renowned for his critical views about the internet. He received much acclaim for his debut book, The End of Absence, a part personal essay, part denouncement of the distractions brought about by digital tech.

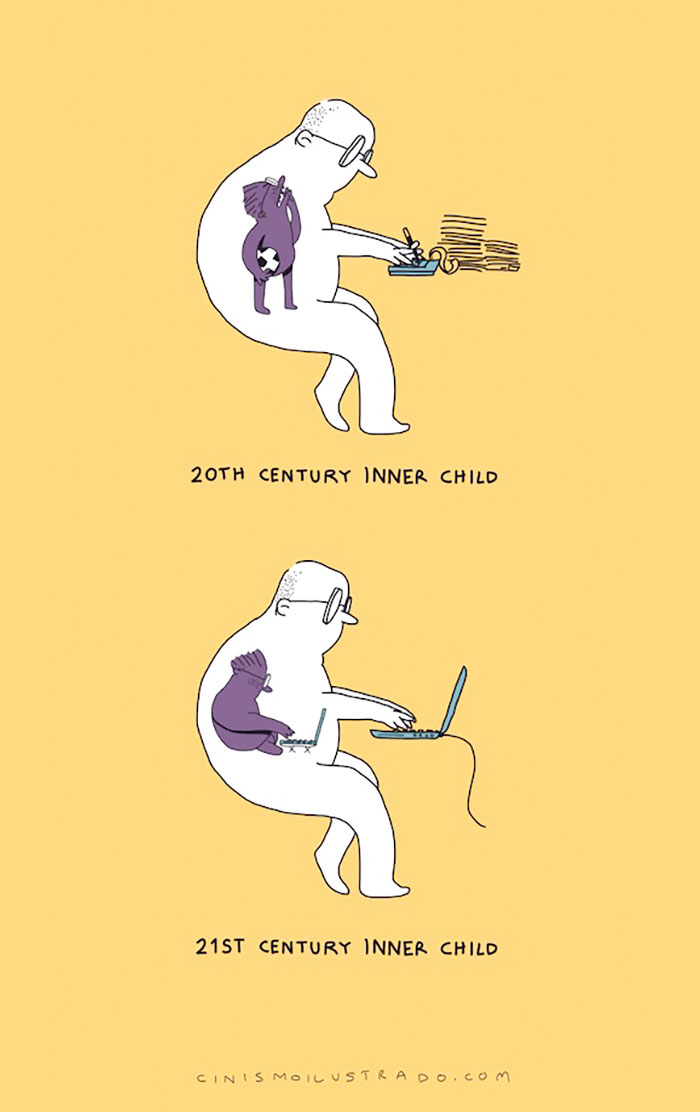

Solitude has a similar premise, arguing that we’ve replaced solitude with our smartphones, trading thoughts for cheap thrills. It will appeal to those who are inclined to let their mind wander: the pensive wallflower, deep-thinker, or perennial navel-gazer. Harris argues that spending time alone is essential for developing certain introspective traits, such as wacky ideas or thoughtful responses. And he writes with poetic flair; for example, his thoughts on the merits of reverie:

“Without daydreams our minds are only parrots – or worse, computers. Daydreams are the engineers of new worlds.”

Or the downside of small talk:

“…adults frown at dinner parties to see their spontaneous thoughts mauled by the wolves of other people’s misunderstanding”.

Of course, Harris is himself an introvert, although he doesn’t mention it. Amongst his many musings, I was frequently reminded of Susan Cain’s bestselling book, Quiet. Both authors champion the value of time spent alone, but are worried that the modern environment is suboptimal for introverts. And it’s the latter point that Solitude really hammers home.

Solitude is a depleting resource

The biggest takeaway from Solitude is how difficult digital tech has made it to be alone. Using the forest as a metaphor, Harris argues that solitude is a depleting resource, at risk of disappearing altogether:

“What we’re beginning to notice, from the midst of this tech-gorged moment, is that solitude is a resource we can either nurture or allow to be depleted. Think of a forest. For centuries, we could walk among dense stands of firs when we chose, or profit from cutting the same trees down without much care as whether nature at large would be materially damaged. Then a line was crossed and we found ourselves starved for green space.”

Harris doesn’t think there are many mental ‘forests’ anymore, because the tech giants – Facebook, Google etc. – are rapidly cutting them down. By deliberately designing addictive services, he argues they are actively undermining people’s ability to withdraw to their thoughts:

“Today, thanks to platform technologies, profit is wrought as much by the dismantling of mental resources as it is by the dismantling of natural resources. We have learned to harvest the solitude of others. Profiteers produce social grooming technologies, and agents of distraction swarm around us. Solitude is consumed and depleted as surely as Brazilian rainforests are toppled…”

This environmental metaphor works because it’s a reminder of the sinister and unsustainable goal of the tech giants: the colonization of our time. This surreptitious aim isn’t even secret, but cloaked in ambiguously worded mission statements, like Facebook’s aim to ‘connect the world’. With Solitude, we learn of what is lost in a world of constant connection.

Ironically, one of these things could be meaningful friendships. According to Harris, social media has made us socially ‘obese’, engorging our neocortex, the social part of our brain. And in the race for Facebook friends, we stretch ourselves too thinly, preferring fleeting connections over genuine relationships. To make matters worse, Harris argues seeking solitude has become abnormal. I couldn’t agree with this more, considering the awkward response I usually get when I share that I’m not on Facebook. Such stigma has carried through into some work scenarios, with recruiters recently claiming that not being on Facebook arouses employer suspicion.

High off nostalgia

Solitude may not be for everyone. It is unabashedly an anti-social book, that socialites will welcome as warmly as a cup of cold soup. Regrettably, Harris doesn’t give the internet its fair due, as he fails to praise social media for connecting niche subcultures and lonely folk to one another. And some of the endeavours Harris undertakes, such as a week of isolation in a British Columbia cabin, are borderline farcical, a fetishized longing for the past.

Harris also stumbles when attempting to find solutions. While he is bold to envisage an alternative internet, that is “slower-growing…one that requires two-way links, so that any online connection would have to be approved by both parties”, he emphatically proclaims depleting solitude to be an individual’s problem. In doing so, Harris cannot help but reinforce the neoliberal ideal that nothing is society’s problem anymore, but an individual’s. Given his environmental analysis, this assertion feels widely out of place. Nothing short of a collective response will curb the industry-wide commodification of people’s time, attention and data.

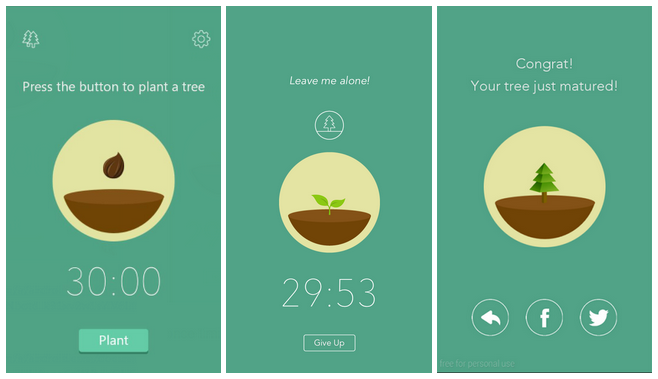

There is another common oversight by popular writers like Harris, who are long on tech-criticism, but short on history. They assume it is tech that is the problem, instead of the ideology that underpins it. So Harris spends too much time pathologizing tech-use, and misses tech-based solutions. A good example is the app Forest, which offers solitude to users by gamifying disconnection.

All in all, Solitude neatly describes the dangers of constant distraction and is a timely reminder of the rewards of time spent alone. Like Susan Cain’s Quiet or Alain de Botton’s Status Anxiety, it is well worth the attention of any contemplative digital denizen. Because, as Solitude cleverly outlines, big tech is forever lurking to get there first.