Zero Time: NZ’s Zero Carbon Act (2018)

New Zealand’s 2018 is the United Kingdom’s 2008. Here, we offer five reasons why the Zero Carbon Act’s time has come.

In thirty years time the 8th of November 2016 will not be remembered as the day the political winds were blustery. It will be remembered as the day the World Meteorological Organization first demonstrated that global temperatures surpassed 1°C above earth’s pre-industrial average for an entire year. ‘Believer’ or not, the scale of the job in front of our policy-makers is unprecedented. The scale of the job in front of the young who elect them is on par.

In a few days, on the 23rd of September 2017, my fellow citizens of Aotearoa New Zealand and I will go to the polls to decide whether to keep the status quo or elect a new government. Following a populist surge from an alluring—albeit untested—opposition Labour leader, a recent poll has the status quo (National) back in front, and one of its former politicians (my stepfather) breathing a little easier. Still, it’s close, and his breathing inconstant. And so it should be. New Zealand’s economy has gone from strength to strength under National’s steer, but all the while, the country’s fallen behind in housing and food affordability, inequality, child poverty, water quality and still lacks smart infrastructure in its largest city. And then there’s climate change.

The good news is that almost ten years after the UK saw cross-party support for climate change legislation, a New Zealand measure tackling climate has finally forged cross-party agreement. The bad news? This is among New Zealand’s youth parties—not yet where it counts. Showing adults the way, New Zealand’s politically immature—including the robotically naïve conservative group the “Young Nats”—have pushed partisan politics aside and propped their support behind the Zero Carbon Act.

The Zero Carbon ‘Act’

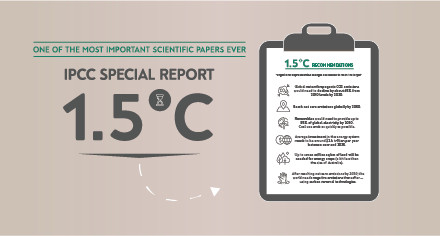

Modelled on the UK’s 2008 Climate Change Act—which has an 80% emissions-reduction target to 2050—the Zero Carbon Act will commit New Zealand to a 100% emissions-reduction target to 2050, ensuring they are carbon neutral by 2050—or thereabouts. This is consistent with the Paris Agreement’s 2015 goal of “achieving a balance between anthropogenic [human] emissions by sources and removals by sinks [e.g. forests] of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century”. A goal, incidentally, that itself has been cast as woefully short. I mustn’t digress though.

The proposed Act can be explored in detail here. In a nutshell, it will require a long-term target to be met through New Zealand meeting five-yearly interim carbon budgets (or “stepping stone” targets) set by its Government—irrespective of who that is at the time. It will also require Government to have a plan. In the words of Generation Zero, New Zealand’s leading progressive political organisation and the ‘Acts’ designer and greatest advocate:

“It sets out a legally-mandated outcome and process, without prescribing specific policies. It combines long-term clarity on policy direction with flexibility in its delivery.”

Flexibility sounds good in theory but it’s even better in practice. In an international energy market where China is ditching coal, not digging it, where Norwegian, French, British and Indian legislatures are preparing moratoriums on internal-combustion transport, where 90% of new power generation in 2015 was from renewables, and where $7 trillion of global energy investment to 2040 will be funnelled into new wind and solar plants, countries have options, and they’re exploring them. When the Zero Carbon Act comes into force, it will bring accountability to New Zealand meeting its international responsibility, but at the same time, will allow its parties—whether The Opportunities Party (TOP) , National, Labour or the Greens—to decide on the details. That way, whatever the measure, whether an augmented Emissions Trading Scheme (TOP and Labour), a carbon tax and dividend (Greens) or a business-as-usual approach (National), government will be held responsible for future irresponsibility.

In June 2017, Sweden passed their Climate Act, pledging to reach net-zero in 2045. The same month, Norway pledged to be carbon neutral by 2030.

It’s Time For NZ to Act

1. We must depoliticise climate change now

Hope and reason will prevail because they always do, but the burning question is when? New Zealand’s government of nine years, National, has blithely bypassed the most important economic, environmental and equity issue in the world, and yes, that means in New Zealand as well. As of today, most of the country’s parties support the Zero Carbon Act: Labour, the Greens, The Opportunities Party (TOP) and even New Zealand First. But as New Zealand’s outgoing Parliamentary Commissioner on the Environment, Dr Jan Wright, stressed recently in her department’s report on climate change, support across all political parties is critical. Why? It’s pretty simple. Because—as Wright confirms—we only have one planet:

“Climate change is the ultimate intergenerational issue, and governments change”.

In New Zealand, an apolitical long-term solution like the one that garnered the support of 493 UK House of Commons’ members (there were only three “noes”) is not necessary, it’s a global necessity. We all know that political distractions like ‘the Donald’, Brexit, and the Great Financial Crisis prevent politics from doing what it’s actually supposed to do. As such, ensuring societal progression on the world’s most “wicked” problem depends on New Zealand—as well as every other country (and companies for that matter)—losing climate policy from the fluctuating whims of its future politicians (and CEOs). To take an all too obvious New Zealand example—Winston Peters likes nothing more than to bend with the breeze.

New Zealand’s next election will be in 2020 but as the international climate community know, there’s only “three years to safeguard our climate”. Initiatives such as Mission2020, Action2020 and numerous other initiatives are rightly putting all their energy into bending the curve of emissions now where “the pre-2020 period will define the post-2020 reality”.

2. Aotearoa’s Inconvenient Truth

Curiously, one of the reasons Brits—including their former Prime Minister David Cameron—were in near unanimity in championing a cross-party approach to climate change was due to Al Gore’s 2006 documentary, An Inconvenient Truth. Of course, there were other reasons: the UK government-commissioned ‘Stern Report’ on climate change in 2006 which highlighted that “strong, early action considerably outweighed the costs of inaction”; the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2007 report on our bleak scientific predicament (yes, it’s got much bleaker); and the fortuitous fact that Lehman Brothers were still three months out from filing for bankruptcy and plunging global markets into recessional retreat. There is no denying it; the narratively impaired issue of climate change had a fleeting moment of heightened political concern in 2008.

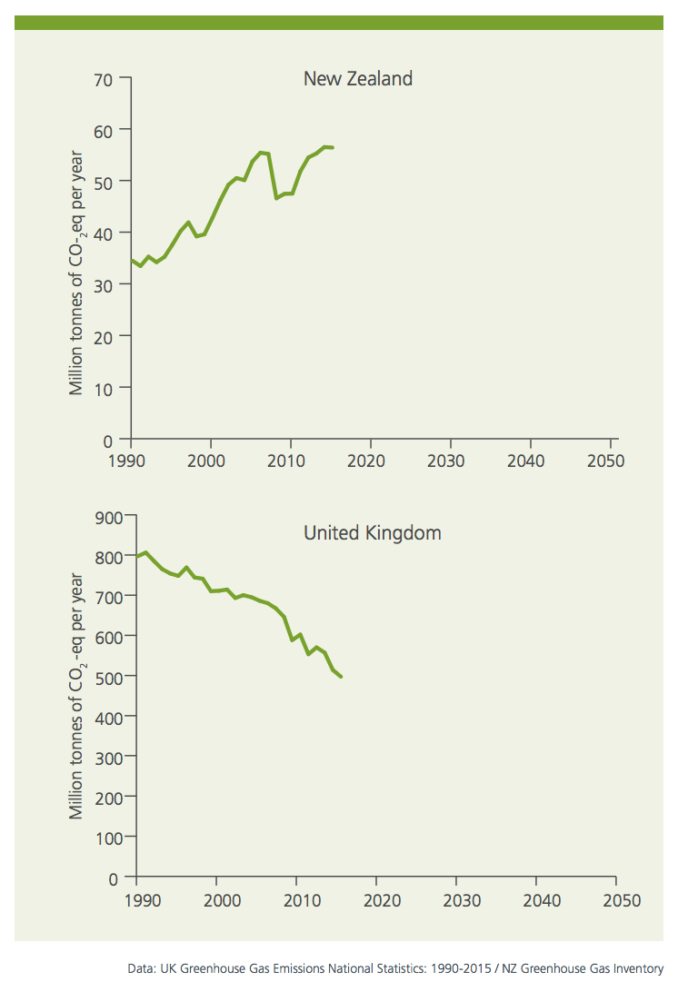

In the year Al Gore’s 2017 An Inconvenient Sequel is making waves, it’s time for the world to face up to Aotearoa’s Inconvenient Truth. Between 1990 and 2015, New Zealand’s net emissions increased by 64%, whereas the United Kingdom’s net emissions fell by 38%.

Net GHG emissions between 1990-2015 in NZ and the UK (Credit: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment)

There are historical “reasons” for NZ screaming upwards (and the UK hurtling downwards) but to put it politely, these are not future excuses:

- Proportionately, New Zealand’s population has grown much more rapidly than the UK’s population over the past 30 years.

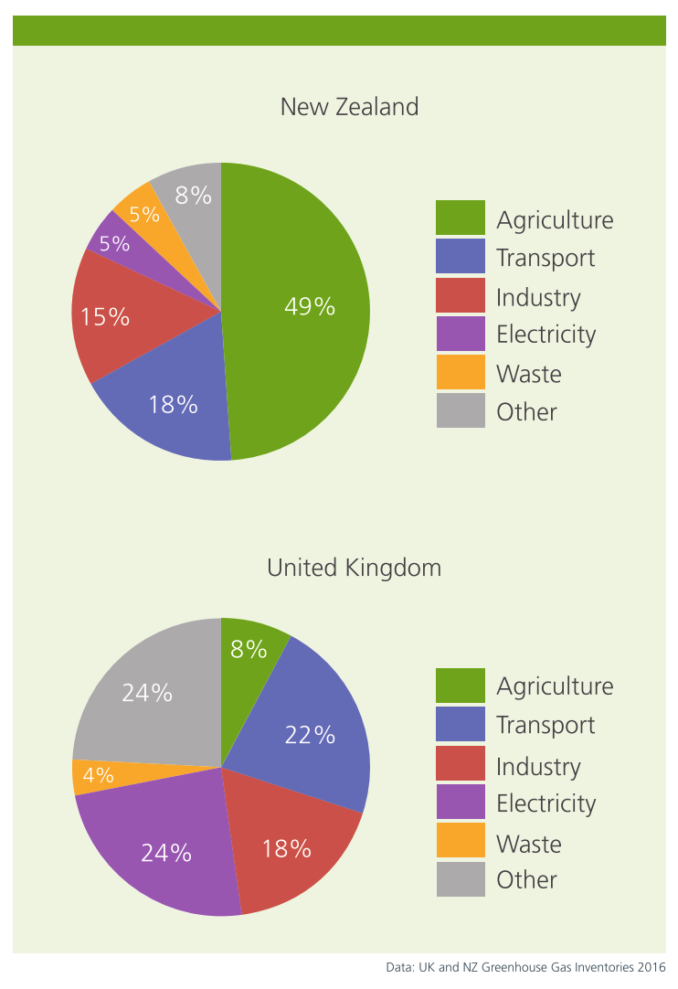

- Compared with the UK, New Zealand’s current ‘emissions profile’ makes it difficult to eliminate ‘low-hanging-fruit’ emissions, such as decommissioning dirty coal-fired power plants—because it only has two.

- New Zealand’s agricultural practices—despite ongoing efficiency and productivity gains—have contributed to a substantial increase in GHG emissions, in large part to an increase in methane production from livestock. A 95% increase in the national dairy herd and a more than five-fold increase in fertiliser application has effects.

These are all immense challenges but since when have New Zealanders not been up for a challenge? Especially when it’s reputational? Or when it’s losing to Australia? In March 2017, London-based economic consultancy, Vivid Economics, produced a report on options for Net Zero in NZ, concluding “it is possible for New Zealand to move onto a pathway consistent with domestic net zero emissions in the second half of the century, but only if it alters land use patterns”. This stinks of inconvenience, for New Zealand’s primary industries would need a major shake up, but as New Zealand’s Ministry for the Environment warned back in 2001, “our clean green image is likely to be worth hundreds of millions, and possibly billions of dollars per year”. Clean and green or lean and mean?

The GHG ‘emissions profiles’ of NZ and the UK in 2014 (Credit: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment)

3. Business, to do business, requires predictability

New Zealand’s brightest new-age economic think tank, Pure Advantage, knows what business needs better than most. Their vast network of business and policy experts advocate solutions based on green approaches New Zealand are already doing—but not doing quick enough. To kickstart New Zealand’s acceleration to a position of competitive advantage on the world stage—in an age where all countries are ratcheting up their strategies to tackle the climate challenge—a legislative measure that eliminates long-term uncertainty is a no brainer. For example, Pure Advantage advance strategies that increase our proportion of renewables, accelerate the uptake of electric vehicles (and their attendant infrastructure), encourage afforestation (e.g. Trees that Count) and promote smart investment in agricultural technology that reduces biological emissions. If you have the time and inclination, check out their impressive microsite outlining New Zealand’s four net zero ‘options’: “Off Track New Zealand”, “Innovative New Zealand”, “Resourceful New Zealand” and “Net Zero New Zealand”. Their preferred? Well, that’s a no brainer.

The Net Zero Act would allow New Zealand to deploy its technology and unleash its innovation without restriction, all within a guided and predictable framework. New Zealand’s most acclaimed international business leaders—the likes of Katherine Corich and Mark Wilson—know this. So do the people who dictate monetary policy internationally. For example, Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, derides the changing nature of climate policy and advances the need—where possible—for devices that are “agnostic” to temperamental mood swings:

“Climate Policy is going to adjust, it is going to be made, it is going to be unmade, it is going to be expanded, contracted, toughened, softened in various jurisdictions at various times around the world. It’s going to change. And that’s part of the issue. This is agnostic, neutral to whatever policies are out there.”

Although speaking in respect of the need for corporate reporting on climate change to address the risks posed by “the tragedy of the horizon”, Carney could just as easily be referring to countries’ long-term legislative endeavours—measures such as the Zero Carbon Act.

4. Prosperity for all

New Zealand is WEIRD. Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic. It’s a developed country. Its cities consistently feature in the top five places on the planet to live. Its institutions are still young and malleable to modernity. Last year, New Zealand was lauded by the Legatum Institute as the most prosperous country in the world, for the fourth year running.

Prosperity brings responsibility though, or rather, it should. Climate change will devastate many of the world’s developing countries (before it devastates its developed ones), including many of the pacific islands north of New Zealand, such as Fiji, Tokelau and Tuvalu. Unable to invest in the infrastructure and resources required to prepare for rising sea levels and storms on steroids—such as what hurricane Irma and Harvey just unleashed on the Caribbean—developing country citizens will be consigned to clean up the mess catastrophes cause. That, or move.

The latest edition of The Economist (16 September 2017) summed it up neatly: “global action on climate must become much more ambitious. Otherwise, large parts of paradise will eventually be washed away”.

New Zealand can help lead the world to mitigate the worst. And it should.

5. New Zealand can pack political punch

Just as smaller, nimbler and more innovative firms will drive the energy transition, smaller countries will lead the policy transition. Costa Rica is small, yet just a few years ago, it harboured the intention to become carbon neutral as early as 2021. While this was later proved to be too ambitious, ‘radical’ environmental legislative measures such as its Payment for Environmental Services Program (PESP) showed the world what can be achieved by ‘small’ countries when long-term thinking and ambition combine. A country of deforestation to afforestation, Costa Rica produced 98.1% of its energy from renewables in 2016, and while it only takes up 0.03% of the world’s landmass, it now contains 5% of the earth’s biodiversity.

Agricultural New Zealand is no rainforested Costa Rica but it has also been cast as small and “over there” by foreigners. That’s not entirely true, as most New Zealanders will tell you. It gave women the vote ‘two’ centuries ago with the introduction of a new Electoral Act (OK, in 1893, but still, before anyone else did), and last century it stood up for that other existential challenge that’s been in the limelight of late: nuclear proliferation. In fact, New Zealand’s 1987 Nuclear Free Zone, Arms Control and Disarmament Act received a 2013 ‘Future Policy Award’ from the UN for its contribution to peace and disarmament.

What’s it to be this century.

The Parting Opportunity

The party that really stood out for me in this election cycle was The Opportunities Party or TOP. Before it began its campaign, it commissioned research to gauge who the average New Zealand voter was. First, it found that 65% of New Zealanders never change their vote. Second, it found New Zealanders decide policies based on:

- what’s in it for me? (39%)

- who’s promoting this policy? (31%)

- who’s paying for this policy? (24%)

- does this policy benefit New Zealand or not? (6%)

On Saturday, a selection of New Zealanders will ask “do these policies benefit the world”? For many others, they’ll subconsciously agree with Robert Dahl that “politics is little more than a sideshow in the great circus of life”. Unfortunately for them, climate change could prove him wrong.