The Attention Merchants

Tim Wu

In the 2016 sci-fi movie Arrival, there’s an intriguing scene that speculates about the effects of learning a new language. A linguist, played by Amy Adams, offers a theory that the language you speak determines how you think. Part of what makes Arrival fun is the implausible places it goes with this. But the idea – known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis – is real and the lesson quite handy: language is a toolbox to unlock new perspectives.

If that’s the case, than Tim Wu’s The Attention Merchants could change the way you see the Internet. It isn’t science-fiction, or about extra-terrestrials – rather, it’s a non-fiction book that offers a new language to understand the economics of the Internet. Reading it will alert you to how Internet really works, and make the whole online experience feel – well, a little alien.

Arming users with new words

This is a book that offers a new phrase or two to impress your friends. But it ain’t Wu’s first rodeo. In 2003, Wu coined net neutrality, a principle that all data should be treated the same. Like a flag on a battlefield, the phrase has united Internet users and rallied them against attempts by Internet service providers to provide preferential access.

Credit: Manjunath Kiran

In The Attention Merchants, Wu arms readers with new phrases to combat a more pervasive commercial force. This is the ‘attention economy’ – identified originally by Michael H. Goldhaber – and here Wu sticks labels on the key players. He calls anyone in the business of attracting people’s eyeballs, ‘attention merchants’. While it sounds like a career for the class clown, it cleverly explains why much of the Internet is free. Attention merchants typically comprise the news, showbiz and social media, and offer free content in exchange for the attention of the audience. Data that is generated during the attention capture is resold to advertisers.

Some may question whether the idea of ‘attention merchants’ is just a kooky way to describe advertising. That may be true, but Wu’s words reflect how big and influential the industry has become. He spends the majority of the book detailing the evolution of advertising, from peddling snake oils to personalized Facebook newsfeeds. It’s quite the history lesson, with a key point being how many industries have turned to harvesting attention for revenue.

Free trade or fair trade?

Once Wu’s vernacular sinks in, you’ll never think about the Internet in the same way again. Firstly, it makes you realize that going online is the equivalent of entering a personalised marketplace where your eyeballs are the hottest commodity. It reminded me of visiting Jemaa el-Fnaa square in Marrakesh, where the possibility of invisibility is zilch.

Secondly, it leads you to question which trades are fair deals or rip-offs. Watching an ad before a free Youtube video might seem reasonable, but how much attention and data should you trade for connecting with a friend you already have? Wu suggests the attention price of Facebook is extortionate, calling it an example of ‘attention arbitrage’:

Having been originally drawn to Facebook with the lure of finding friends, no one seemed to notice that this new attention merchant had inverted the industry’s usual terms of agreement. Its billions of users worldwide were simply handing over a treasure trove of detailed demographic data and exposing themselves to highly targeted advertising in return for what, exactly? The newspapers had offered reporting, CBS had offered I Love Lucy, Google helped you find your way on the information superhighway. But Facebook? Well, Facebook gave you access to your “friends.”

A success of The Attention Merchants is that it exposes the inequity of the attention marketplace. Wu suggests that the Internet is a place of secret commerce where all prices are fixed, and terms of agreement non-negotiable. To return to the marketplace metaphor, it’s like bartering in a bazaar without the option to haggle.

It’s time to update the rule book

Of course, the Internet is not just a marketplace, but infrastructure for people’s everyday lives. As such, another lesson from The Attention Merchants is that the rules governing the Internet need an update. Surprisingly, Wu is less concerned about rules pertaining to users, perhaps having the foresight to see that pending changes to data protection laws will give them greater bargaining power.

Instead, Wu’s sympathy is for the attention merchants themselves. In his eyes, they’re all after a slice of the same pie, meaning all media companies – be it high-brow, low-brow, showbiz or sports – now compete against each other, forcing them to a race to the bottom for people’s attention. If you’re wondering how low this can get, consider that professional brat “Cash Me Ousside” Danielle Bregoli is getting a new reality TV series. How bow dah?

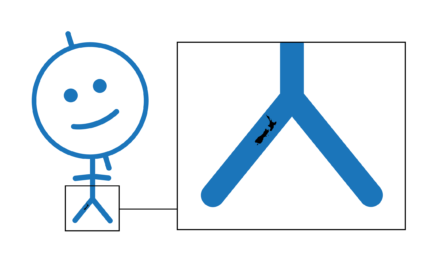

The problem, according to Wu, is that the law doesn’t recognise attention merchants as competitors. This leaves Google and Facebook free to gobble up the ad-money and forces traditional media to turn to more dubious means to source funding.

An example of this oversight is in New Zealand, where the Commerce Commission recently declined a merger of the two largest media companies. While the Commission was right to acknowledge such a move would be antithetical to news competition, it failed to acknowledge the attention competition of Google and Facebook. It wasn’t even on their radar.

Ad-blockers are invisibility cloaks

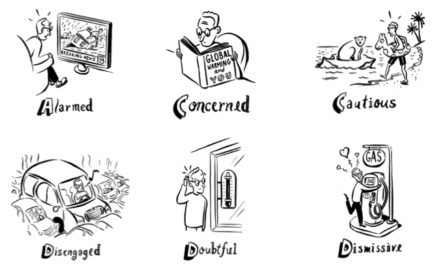

It’s clear Wu is concerned about the attention economy, but it’s not all doom and gloom. Historically, he argues, the audience’s tolerance for advertising swings back and forth like a pendulum. And with Apple’s iOS and other ad-blocking software like the web browser Brave, we’re entering a period of ad protest. These technologies offer a kind of invisibility cloak when browsing online, to shield users from attention thieves.

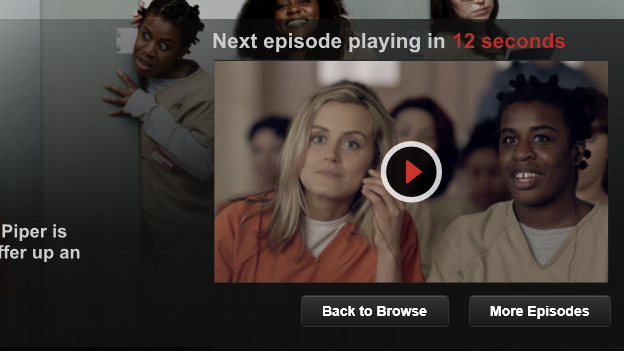

What’s less convincing is Wu’s optimism that a surge in subscription-based businesses will stem the growth of the attention economy. His white knight is Netflix, which he claims respects audiences attention by having no ads. This may be true, but some of its key design choices, like auto-play functionality, are deliberate, to hold users’ attention. Further, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings recently claimed that the streaming giant’s biggest competitor is none other than sleep itself. This isn’t a company interested in respecting people’s time.

Wu’s best suggestion is his most ambitious: a human reclamation project for attention. It’s a long term solution, and could materialize in the form of new industry standards or digital ad free spaces. Realistically, it’s not something that will gain legs until more confronting technologies like augmented reality go mainstream.

In the meantime, Wu joins names such as Tristan Harris, Matthew Crawford and Mary Aiken as critical voices in reforming the attention economy. It could be a project of a generation. Thanks to The Attention Merchants, we at least have a toolbox to recognise we need one.