Trump & The Paris Agreement: The Bad, The Good & The Ugly

Back in 1961, JFK famously declared the US would take up global challenges—like going to the moon—“not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win”.

Back in 1981, Ronald Reagan symbolically removed Jimmy Carter’s solar panels from the roof of the White House because they were “a joke”.

Back in 2001, George Bush rejected the Kyoto Protocol—the first multilateral international treaty that sought to address climate change mitigation commitments—because it was a joke.

In 2021, Donald Trump will have removed the US—the world’s largest historical greenhouse gas emitter—from the Paris Agreement, that sovereignty-respecting, painstakingly-nuanced agreement that brought 195 countries to the table to address the “greatest challenge of our time”.

JFK and jokes aside, let’s unpack what’s happened in three ‘choose-your-adventure’ parts. If you’ve never heard of the Paris Agreement, start with Part III. For those who are familiar, start with Part I. If you’re up for the full monty, well, then that’s great:

Part I: The Decision: Trump and his environment, the deal-breakers.

Part II: Leadership From Where it Matters: Cities, Companies & Civil Society. The good, possibly great news.

Part III: The Paris Agreement: Plenty of people have never heard of it. I’m taking that as the first positive: ‘bad’ publicity will also mean great publicity. This is a run down of exactly what it is, and why it was such a remarkable achievement.

_____

Part I: The Decision

Let’s clear up what everyone’s already thinking: Trump’s decision to go against the will of the American people and withdraw was not about climate change and nor was it about the Paris Agreement. It wasn’t even about jobs. His decision was an attempt to show the world who’s boss, it was to give congress the middle finger for not dancing to his domestic agenda and at the same time, show his die-hard constituents unwavering loyalty. The evidence of Donald Trump looking at the evidence for climate change is non-existent. No scientists were consulted, and the one study (from MIT) that Trump mentioned was wholly misrepresented, a fact pointed out by its author hours later.

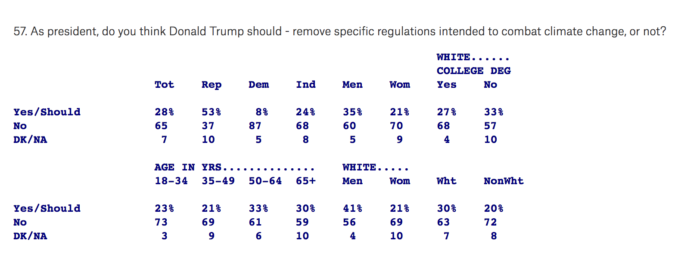

2017 Poll: 65% of Americans oppose Trump’s climate agenda. (Source: Quinnipiac)

Trump’s speech struck me as a sort of ‘justification of opposites’:

- “Therefore, in order to fulfil my solemn duty to protect America and its citizens, the US will withdraw from the Paris climate accord”. Wrong on every count: economically, environmentally and with respect to national security, the citizens of America will be less protected.

- “It’s very unfair at the highest level to the US”. Nope, it’s actually exceptionally generous given how responsible the US is. As explained below in Part III, determining responsibility is fraught with difficulty, but given that every other country yielded to the demands of the US during negotiations, the Paris Agreement could actually be called the ‘US Agreement’.

- “It’s less about climate and more about other countries gaining a financial advantage over the US”. Wrong, other people don’t just think about money, they also think about livelihoods, prosperity and intergenerational equity.

- “Begin negotiations to re-enter…an entirely new transaction… something we can do much better than the Paris Accord”. No, there’s no beating the Paris Accord sorry Donald. A quarter of a century of trial and error finally got us the Paris Agreement. We don’t have another day to waste, let alone another quarter of a century.

- “I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburg, not Paris”. Yes, you were, but Pittsburg ain’t with you, they’re with Paris:

Unlike other decisions, Trump actually thought this one through, but with some help.

Trump’s Close Environment

On the one hand, Trump had people close to him urging him to stay in despite his campaign pledges, including Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson and daughter, Ivanka—whom Breitbert News saw as the biggest risk to their agenda. He also had global CEOs from the world’s largest companies including Apple, Google, PG&E Corporation, Shell and BP, and prominent members of his Business Council, including Tesla’s Elon Musk, warning him of the moral and business consequences of withdrawing. Musk—for some a utopian future president of the US—is livid.

On the other hand, Trump was consulted by a group of die-hard Republicans, led by his chief strategist, Steve Bannon, who vigorously lobbied for withdrawal from the Agreement. Bannon, the smiling ideologue, who cheered Trump on during the announcement, must have cast a thought for what his former organisation, the alt-right Breitbart News, was stewing up as Trump spoke. For the record, amongst others, they ran this: ‘Democrats Agree With Putin, Communist China on Paris Climate Change’.

Standing Ovation: Trump’s Chief Strategist, Steve Bannon, is at far left

Given that I’ve already written a previous piece on the other characters in Trump’s Environment, instead of concentrating on the rest of that group individually, a collective appraisal seems in order.

The Republican Party

Three weeks ago, Noam Chomsky labelled the Republican Party “the most dangerous organization in human history”. He might be a left-leaning academic from way back, but before you go laughing him off, as the most prolific public intellectual of our time, he also might be worth listening to for 1 minute and 35 seconds:

One week ago, 22 Republican Party members, all oil-and-gas stalwarts—and yes, all men—sent ‘The Honourable Donald J. Trump’ this letter urging him to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Collectively, the King CONG (Coal, Oil and Natural Gas) industries have donated $10,694,284 to these 22 senators over the past three election cycles. Below are their names (and here’s a sample of the evidence):

- James Inhofe, Oklahoma

- John Barrasso, Wyoming

- Mitch McConnell, Kentucky

- John Cornyn, Texas

- Roy Blunt, Missouri

- Roger Wicker, Mississippi

- Michael Enzi, Wyoming

- Mike Crapo, Idaho

- Jim Risch, Idaho

- Thad Cochran, Mississippi

- Mike Rounds, South Dakota

- Rand Paul, Kentucky

- John Boozman, Arkansas

- Richard Shelby, Alabama

- Luther Strange, Alabama

- Orrin Hatch, Utah

- Mike Lee, Utah

- Ted Cruz, Texas

- David Perdue, Georgia

- Thom Tillis, North Carolina

- Tim Scott, South Carolina

- Pat Roberts, Kansas.

Completely oblivious to the risks they pose to the rest of the world, this is the Republican Party.

The story of Trump thus far has been about exactly that—Donald Trump and no one else—a spasm of populist dribble with little to no ideological core. But when it comes to climate change denial—a bedrock of Republican and conservative politics for the last 20 years—Trump and the Republican Party are a match made in hell, for the world that is. They live in a fact-free zone, citing fringe studies funded by the nefarious CATO or Heartland Institutes and have the nerve to completely misrepresent an MIT study as the only scientific basis to remove themselves from Paris.

They’ve even started their own Wikipedia: Conservapedia.com. Read about ‘The Donald’ or their interpretation of evolution. A better use of your time, however, will be to read the study of climate change denial conducted by Aaron McCright and Riley Dunlap: “Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States”. It says two primary things:

- Conservative white males are more likely than other adults to deny the existence of a scientific consensus on climate change (58.8% and 35.5% respectively);

- Among conservative white males, there’s a positive correlation between a self-reported understanding of the science of climate change and its subsequent denial.

The second point is crucial when it comes to assessing Trump’s environment. Many of these men, if not all of them, will have looked into the ‘science’ of climate change. Incidentally, Conservapedia describes climate change as follows:

“The new name used by liberals for their global warming hoax, which they coined as it became obvious that there is no crisis in global warming”.

Even if they’ve actually looked at the real science of climate change, as McRight and Dunlap reveal, an intimate knowledge of climate change among older conservative men tends to harden their opposition to it. This seems counterintuitive at first but not when it’s given a second thought. Every solution to climate change challenges the very worldview of these guys: energy regulation, government intervention, intrusions behind company veils, “confiscation”, international environmental cooperation, you name it.

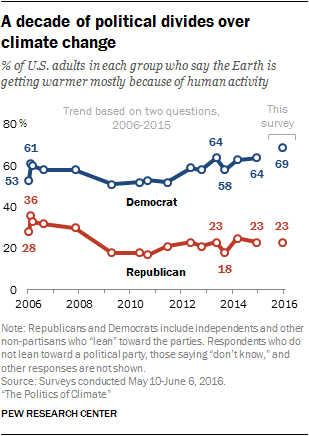

2016 Survey: The Republican planet. (Source: Pew)

Trump’s Not-So-Close Environment

Finally, there’s the people not so close to him, but who command enormous respect internationally. He effectively slapped the Pope in the face with the encyclical on climate change he received from him at the Vatican last week. He gave Barack Obama another ‘I’ll show him who’s President’ kick in the guts (Obama replied with this rare public condemnation of his successor’s decision). He gave Emmanuel Macron an ‘I’ll get him back for that handshake’ (Macron’s reply put Theresa May’s “disappointment” to shame in a television statement). Most curiously, he gifted Chinese President Xi Jinping a golden opportunity, ceding the economic and ‘moral’ leadership of the world to him. That may not be an overstatement.

_____

Part II: Leadership From Where it Matters

As Trump was preparing to pull out of the Paris Agreement in Washington, something remarkably ironic was happening over in Texas. Shareholders in Exxon Mobil, the most obdurate climate-change corporation on earth, supported a ‘historic’ motion to assess the risks of climate change in their business. It sounds insignificant, but it’s anything but.

Under investigation by state prosecutors in New York for misleading investors on the issue, the sixth biggest company in the world now has to consider the risks of climate change and how efforts to mitigate those risks will impact their business. Last year the same motion gained only 38% of shareholder support—this year it gained 62%. Exxon will now join the ranks of other King CONG companies, such as BP and Shell, who’ve succumbed to pressure from NGOs and have integrated the risks (and opportunities) of climate change within their business case.

The Zeitgeist Has Shifted

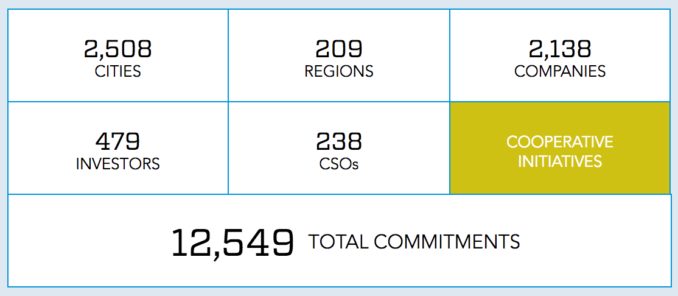

Over recent years, cascading across states, cities, corporations and other civil society groups, a proliferation of voluntary initiatives – all aimed at addressing climate change – have increased as quickly as the price of solar power has decreased. Touted for years as an important contributor to mitigating climate change, the mobilization of these ‘subnational actors’ was considered vital to overcoming the ‘emissions gap’. Now they’re indispensable, and they’re moving.

The Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action (NAZCA) (Source: UNFCCC)

Domestic Leadership

In the aftermath of Trump’s announcement, Californian Governor, Jerry Brown, booked a flight to China. Landing on Saturday to affirm #livebyparis, Brown declared that “China is moving forward in a very serious way… And so is California.” On the other side of the Divided States of America, New York Governor, Andrew Cuomo, announced the formation of the United States Climate Alliance: a pact to cut greenhouse gases in line with Paris. Already, the states of New York, Washington, California, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, Oregon and Hawaii—whom represent more than 30% of US GDP—have signed up.

The former mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg, now president of C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, a coalition of 90 global cities pushing the Paris agenda, conveyed the feeling of resilience:

“The US will meet our Paris commitment and through a partnership among cities, states, and businesses, we will seek to remain part of the Paris Agreement process… The American government may have pulled out of the agreement, but the American people remain committed to it – and we’ll meet our targets.”

Bloomberg continued, suggesting, by redoubling their climate efforts, cities, states and corporations could achieve, or even surpass Obama’s pledge to reduce America’s emissions 26 percent by 2025. Ambitious? Yes. Achievable? Not yet.

International Leadership

This was always going to be the critical question, and until the dust settles, we won’t know for sure. But the signs have been exceptionally promising, perhaps illustrated best by:

- China: Premier Li Keqiang has reassured that China will “forge ahead” with its “international responsibility”.

- India: Prime Minister Modi declared his country will go “above and beyond” their Paris commitments. This comes after recent government announcements that they’re considering committing to an all-electric car fleet by 2030.

- Europe: Emmanuel Macron’s making a habit of summing things up best:

- Japan: Their Environmental Minister, Koichi Yamamoto, found particularly profound words: “It goes against wisdom cultivated by mankind”.

- The (other) United States of America: Former Secretary of State, John Kerry, doing well to contain his exasperation, declared Trump’s “gross abdication of leadership” as “one of the most cynical and frankly ignorant, dangerous and self destructive steps that I’ve seen in my entire public life”.

With cautious optimism, I contend that the empty rhetoric that has perennially plagued climate change is over. Galvanised by a clown in the White House and a deep resolve on the subnational and international stage, Trump’s decision will be an ally—not a frustration—of enhancing action to combat climate change. Most importantly, Arnie agrees:

_____

Part III: What’s So Special About the Paris Agreement Anyway?

By accommodating what’s scientifically necessary with what’s politically possible, the Paris Agreement represents the reality of global governance today. The Agreement marries ambition of commitments with the recognition of state sovereignty, and in doing so, strikes a delicate balance between what a nation should do and what it can choose to do.

As Daniel Bodanksy noted when the Paris Agreement’s predecessor, the Kyoto Protocol, was taking its final breaths long before the triumph at COP21, the “role of the climate regime is not to define what each state must do, but rather, to help generate greater political will by raising the profile of climate change”. In other words, by allowing states to determine their own mitigation commitments (called nationally determined contributions or NDCs) the Paris Agreement—unlike the Kyoto Protocol before it—ensures the autonomy of each nation is guaranteed. However, it qualifies this freedom by strongly urging nations to progressively advance action to combat climate change, and crucially, to publicise these advancements.

The following are a few of the Agreement’s key components (with some Trump commentary to boot):

The 2°C Goal (forget about 1.5°C)

Paris’s raison d’être is to keep global average temperatures “well below” an increase of 2.0°C by the end of the century (as compared with the pre-industrial period). Anything beyond 2°C—which we’ll exceed even if all countries (including the US) meet their current commitments—we will likely, and the next generation will certainly, bear witness to significant sea-level rise, dramatic changes in weather patterns, global food and water shortages, increased human migration, and all in all, a steaming pile of shit. Our descendants are in for a rough ride regardless, but if we don’t act now, and if we don’t get all our shit together by 2020, many won’t even get to start their ride.

Critics readily point out that the 2°C target is arbitrary and unrealistic, but for us, it’s a starting point; an easily understood objective that, before Paris, may as well have been anything. The aspirational 1.5°C target was included much more to assuage small island states than to appeal to reason and as we approach 1°C, the science implies a median warming of 2.6–3.1°C by 2100.

It’s Voluntary (kind of)

To make up for being ‘non-binding’, the Paris Agreement is full of aspirational language like “highest possible ambition” and “as soon as possible”. Thanks to the three biggest emitters—the US, China and India—demanding no obligation to achieve any particular result, the agreement instead relies on obligations of conduct (i.e. implementing strategies to reduce emissions) coupled with good faith expectations of result (i.e. achieving those strategies). So, while voluntary, the Paris Agreement incorporates ‘obligatory’ elements. For example, having pledged 26 to 28 per cent emission reductions by 2025, the US would have been under mandatory obligations of conduct to pursue domestic mitigation measures, with the aim of achieving its pledge.

Of course, Trump wants neither to commit nor to pursue the current US pledge. But even less appealing for Trump was the prospect of contributing to what’s called the ‘Green Climate Fund’.

Finance (the ‘Green Climate Fund’)

While not in the Paris Agreement itself (rather the COP21 decision that accompanied it), all developed countries committed to providing “urgent and adequate finance and technology support”; that is, at least USD100 billion annually for mitigation and adaptation activities by 2020, “taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries”.

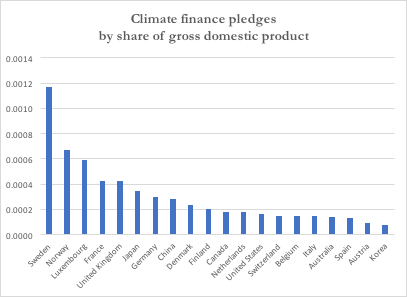

$100,000,000,000 is a lot of money per year; even for Donald Trump. Only ‘responsible’ for providing a proportion of this fund (Obama had already paid USD1 billion of a USD3 billion pre-Trump commitment), Trump is turning his back on the other 43 governments who’ve pledged to contribute to the Fund—including nine developing countries.

A sign of things to come: China ahead of the US (Source: ThinkProgress)

Transparency Trumps Punishment

Rather than crack down on states when they fail to meet their targets after the fact (there’s no defined punishments to date), the Paris Agreement proactively seeks to ensure all states rigorously document what they plan to do, and what they actually do. ‘Oversight mechanisms’—including ‘Technical Expert and Peer Reviews’—form the core accountability mechanisms of the Agreement, to allow collective reporting to encourage and ‘naming and shaming’ to deter.

In 2018, nations will reconvene to take stock of how everyone is doing, collectively, in working towards the goals. These discussions will then help everyone form their next pledges, due in 2020. This pattern of reporting, discussion, progress checking, and lodging new pledges—designed to ratchet up ambition—is repeated at five year intervals from there after.

Notably, a ‘Global Stocktake’ to gauge collective progress, allows a space for science—real science—to inform how the international effort is faring; that is, are we on or off track towards our 2°C target? Trump will hear of the first one of these from the Trump Tower, not the White House, in 2023.

Some believe transparency offers too thin an institutional mechanism for an agreement as important as Paris, but for better, not for worse, it’s the best a diverse 195 countries could muster.

Exiting the Agreement

Article 28 sets out the conditions for (US) withdrawal:

- “At any time after three years from the date on which this Agreement has entered into force for a Party (for the US, November 4, 2016) that Party may withdraw from this Agreement” +

- “Any such withdrawal shall take effect upon expiry of one year from the date of receipt of the notification of withdrawal”

- = Four Years (for the US, the earliest they can withdraw is November 4, 2020)

- November 4, 2020 is one day after the next US presidential election on November 3, 2020.

The Heritage Foundation (for me, the worst organisation on the planet), have lobbied Trump for an even more extreme proposal: the US removal from the UNFCCC—the underlying framework convention for international cooperation on climate change—which has a one year notice period. They wrote an 8 page report on why last week.

Differentiated Responsibilities

The justice of climate change responsibility is a series of posts in itself, so an anecdote will help make my point. Last night, someone I’d just met overheard my buddy and I chatting about Trump’s decision. On his third attempt to capture our attention, I finally understood what he was saying: “Trump made the right decision because of China”. He got our attention. “It’s unfair that China can build coal-fired power plants month after month and in the meantime, the US is prohibited from doing so”. Not exactly right, but he was making a fair point, albeit without historical or contemporary context. The agreement acknowledges that those responsible for the most emissions historically (developed and historically rich nations), should cut back more ambitiously than those who’ve emitted less historically (developing and emerging economies, including China).

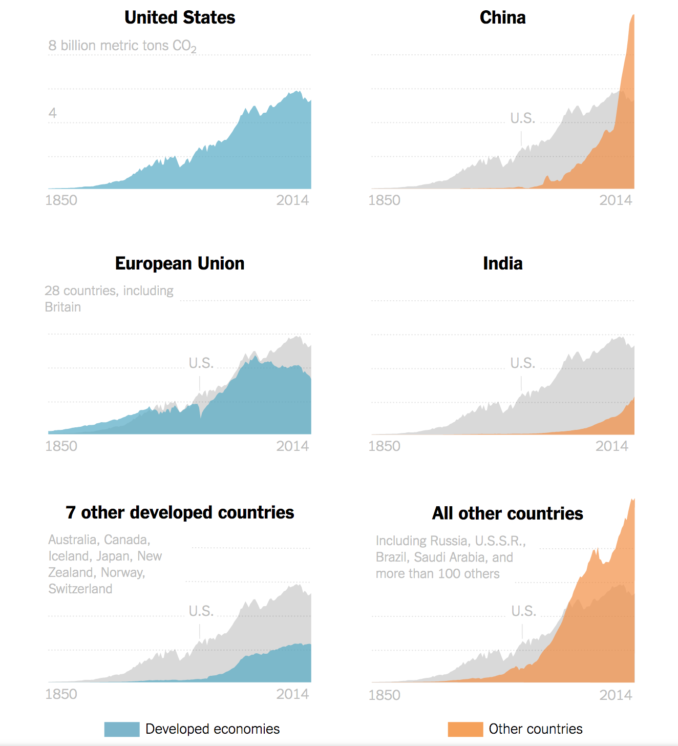

Historical Emissions: China, India and other countries compared to the US (Source: NY Times)

People should be forgiven for forgetting the vast differences in historical emissions between countries. Moreover, due to our different understanding of justice and responsibility, widely divergent opinions abound on how to tackle it. In fact, this is the very reason it’s taken so long to get to an agreement worth more than the paper it’s written on.

A Major Leap for Mankind

Against all odds, the Paris Agreement overcame irresolvable disagreements between Developed and Developing countries to provide a little of something for everyone: adaptation provisions for small island nations, finance provisions for least developed countries and flexibility for large developed countries. Crucially, this encouraged developing countries (including India and China) to set their first emissions targets, joining developed countries who had signed up to emissions targets under the Paris Agreement’s predecessor (the Kyoto Protocol).

The agreement was brokered in the dying hours of COP21 in Paris to deserved fanfare. There was more than sheer compromise involved though. Experts like Lavanya Rajamani helped draft an agreement of astounding subtlety, the US’s demands were begrudgingly accommodated by all other countries, and above all, the “irresistible political momentum” had by then built up so profoundly, the 2015 Paris Agreement was swept across the finish line.

After the disappointment of Hopenhagen in 2009—which quickly became Nopenhagen—it really was a “monumental achievement“. For former French President, Francois Hollande, it was even a “major leap for mankind”.

JFK’s speech was back in business, it seemed.

Thanks for providing me with an intellectual scrutiny with which I can argue my agreement on this topic. Langa, your late father would be so proud of you.