Gear change: Getting a grip on the fact(s)

This article first appeared on Pure Advantage.

The New Zealand Climate Change Commission (CCC) shortly releases its draft emission budgets for the next 15 years. When the advice is formally presented to the Ardern government, this seemingly innocuous exchange will set in motion the biggest economic transition in New Zealand’s modern history and spark a public conversation that’s bound to get colourful quickly. Journalists Marc Daalder and Charlie Mitchell think the advice is likely to ‘shock’ the nation. That’s a profound understatement.

The CCC will release three successive draft budgets: 2022-2025, 2026-2030 and 2031-2035. Once the advice is officially firmed up, the Labour government isn’t legally mandated to adopt the budgets or policy recommendations, yet saying thanks but no thanks would be fatal — and not just for our goal of net zero CO2 by 2050. For a start, our climate credibility would be further shot — it wouldn’t just be Greta Thunberg firing tweets at us. More importantly, it would undermine the trust that has to be forged between the government and independent CCC. On its very first test.

What is the Climate Change Commission likely to say?

The low-hanging fruit for decarbonisation in our country is a peculiar specimen. For most nations, it’s removing fossil fuels from electricity systems, but by fortune of geography and political inheritance, that process is almost complete here in Aotearoa. (As #6 above illustrates, the potential for further electricity decarbonisation is derisory relative to other sectors.) And because agriculture has been kicked into the long grass for a few more years, reducing GHG emissions in New Zealand means tackling that other culturally sacred and politically booby-trapped sector: personal transport.

The road of least resistance, culturally and politically, has for years been to build more and more roads. Given this reality, rather than fight a losing battle against New Zealand’s low-density population, lousy intercity transport options and deeply embedded culture of car ownership, New Zealand is left with a single option. It has to ‘do a Norway’ and electrify personal transport — but by more aggressive means.

Like New Zealand, Norway has abundant renewable foundations: almost all of its domestic energy comes from hydropower. But unlike us, the Norwegian government has invested heavily in financial incentives and electric vehicle (EV) infrastructure. It started early: a 25% sales tax was removed from new EV purchases 20 years ago. In 2005, EV drivers were permitted to use bus lanes. Last year, Norway — by no means a climate saint in other respects — became the first country to reach over 50% electric new car sales. Notably, it has a population of about 5 million.

So what are Aotearoa’s options?

The Ministry of Transport is due to present its Transport Emissions Action Plan (TEAP) in June this year. The CCC is about to confirm that TEAP can’t just tinker around the edges with Road User Charge exemptions and $6 million a year for EV charging stations.

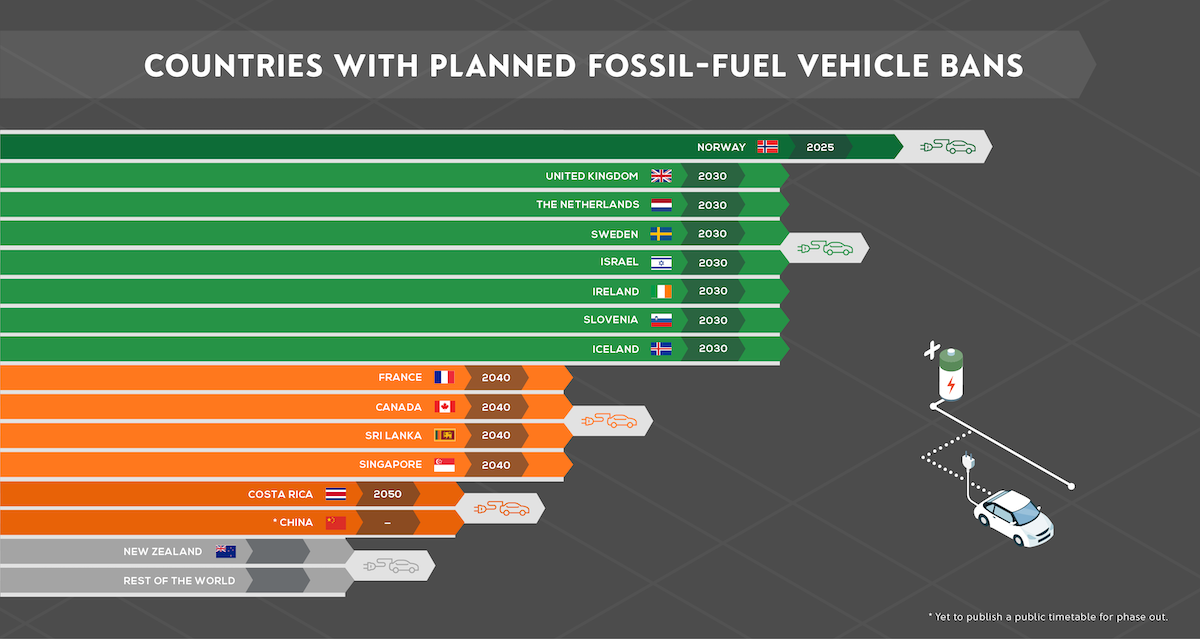

1. Implement a phase-out date for new fossil fuel-powered light vehicles by 2030

When my step-father imported two petrol cars from the UK to New Zealand in 2017, I warned him that they were entering their final decade of dominance. Turns out he brought them to the right country. The UK will ban the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles from 2030, with a five year grace period for hybrids. Other G20 nations have also committed to phase-out dates, including Canada, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Israel, and more recently Japan and Egypt. California will phase them out by 2035.

New Zealand, on the other hand, doesn’t even have a public conversation about it. But there’s been a private one: the Ministry of Transport found that banning the import of fossil fuel vehicles by 2035 would have a NZ$2.26 billion net benefit and avert 27m tonnes of CO2 (one-third of our annual emissions).

It’s not just MoT’s recommendation. In its 2018 report, the Productivity Commission agreed that to slash emissions and save New Zealanders money, all new vehicles entering the fleet needed to be electric by 2030.

In Auckland alone, to deliver its climate action framework, 500,000+ vehicles need to be electric by 2030. Promisingly, EVs should reach price parity with fossil fuel vehicles in about 2025, but that’s not good enough if we want to bend the curve on light vehicle emissions. The strengthened ETS might make fuel slightly more expensive, but relying on the bluntness of the ETS and the magic of the market isn’t going to cut it. Moreover, even a NZ carbon price of $100 — four times what it currently is — would only cut transport emissions by 11% by 2030.

Like the controversial oil and gas drilling ban, we require a bold but unpopular steer from central government. A phase out date could incorporate caveats to keep some parties happy, but it would signal the direction of travel for investors and boy racers. Without it, in a best case projection — MoT’s Fast Uptake scenario — just 23% of our light fleet will be electric by 2030.

2. Reintroduce the feebate scheme

The failure of the previous government’s flagship EV scheme — which was to be revenue-neutral by placing fees of up to $3,000 on high-emitting vehicles to subsidise the purchase of EVs by up to $8,000 — means Aotearoa effectively still has no road emissions policy. Mothballed by NZ First last term, it should be resurrected. Supported by the New Zealand Motor Industry Association, while it does not have potential to slash emissions (1.6m tonnes of CO2e over twenty years, according to a Ministry of Transport analysis) it would have a net present value of $413m. Most benefits would fall to motorists in the form of fuel savings.

3. Fast-track the Clean Car Standard

Aotearoa is only one of three OECD countries without fuel efficiency standards. The Ministry of Transport estimates that Labour’s proposed Clean Car Standard could save an average Kiwi family almost $7,000 per vehicle over its lifetime or $3.5bn across New Zealand as a whole, with a cost benefit ratio of 3:1. It was estimated that it could reduce the average emissions of vehicles entering our fleet by 40% by 2025. That’s a lot.

In comparison with other transport policies, performance standards are politically quiet to pass and proven to cut emissions. This one falls in the no-regrets basket— for governments and political parties alike.

4. Consider a ‘cash for clunkers’ scheme to pay low-income Kiwis to scrap their old, high-emitting cars.

New Zealand’s existing fleet of 5m light vehicles should be tackled as well. Established in 2009 as a stimulus measure after the GFC, the $2.85bn cash for clunkers programme in the US delivered rebates to 680,000 people to replace their old clunkers with new vehicles, reducing emissions, increasing efficiency and slashing fuel costs.

5. Invest in our electricity ecosystem

To stay abreast with an eventual en masse move to EVs, an expected 70% increase in electricity demand by 2050 and meet the Government’s 100% renewable electricity by 2035 commitment, massive investment is required. And not just in the deployment of EV charging stations. According to Transpower CEO Alison Andrew, NZ requires 40 new grid connected generation projects by 2035, 30 connections to accommodate increased electricity demand and 10-15 new transmission interconnections.

What can you do?

- Beep the horn. The most important thing anyone can do about climate change is to talk about why it matters and what we, as a nation, should be doing about it. Individual action that leads to political action is the most valuable pursuit when it comes to climate change.

- Think twice before buying that new Ford Ranger. Globally, emissions from SUVs have nearly tripled over the past decade. In 2020, CO2 emissions fell sharply across every sector except for one. You guessed it. Remarkably, the IEA even estimates that the increase in the overall SUV fleet in 2020 cancelled out the declines in oil consumption by SUVs that resulted from Covid-related lockdown measures.

- Thinking about buying a new car? Buy an EV. Take a look at Ecotricity’s Electric Vehicle Buyers Guide to find out what EV might fit the bill.

- Jump on the bike. Seriously. Poet William Saroyan once described the bicycle as ‘the noblest invention of mankind’. In 2019, the Bicycle Cities Index ranked Auckland the best large city in the world for cycling. And that was before $708m was allocated to public transport, including cycleways.

- Support the 1Point5 Project. Driven by Dr Paul Winton, this campaign is determined to radically reduce NZ’s emissions by 2030 through decarbonising transport and investing in urban alternatives to driving.

Curbing the culture war

A useful lens for thinking about New Zealand’s decarbonisation journey comes from policy expert David Hall’s call for a careful revolution. The worst thing that the world (or New Zealand) could do, Hall warns, is to ‘do nothing about our rising emissions. But the next worst thing is to provoke popular resistance to climate action.’ The gilets jaunes protests that erupted in France provide a lingering example of where a policy aimed at tackling emissions became the catalyst for a political maelstrom. The answer instead lies in a just transition, where people who are most affected by major policy change, especially those in low-income brackets, are not just considered, but compensated, for example through social supports such as retraining. For road transport, a just transition means that any policy that fast-tracks the penetration of EVs should, above all, not be economically regressive.

In the year the UK hosts the biggest climate summit (COP26) since Paris in 2015, and with a new Biden administration not shy of reasserting itself on the climate stage, Aotearoa will not be alone when it chooses policy action. But when Ardern’s government takes the plunge, the burning question is can it bring most New Zealanders along for the ride? On what is very shortly about to become a noisy two-way street.