Communicating climate change: beyond the psychology

BY BRONWYN LO

Bronwyn Lo goes deeper than just the psychology. This is Part II in her series on climate change communication in the digital age. It’s a tough gig out there, but it’s made easier if you know what you’re doing.

Last week was huge. The challenge now is to sustain the interest and conversation in day-to-day life, and to translate them into action: political, structural and individual. If you missed it, four million students and workers took part in the global climate strikes last week, supported by schools, businesses and media outlets, in demonstration of the breadth, height and impacts of climate change.

The difficulty of achieving what must happen next shouldn’t be underestimated. There have been missed ‘turning points’ before, and there are many barriers — psychological and situational — to people maintaining or accepting climate change as a priority issue. Climate change is, for all its reach, a topic that’s peculiarly easy for the ordinary person to ignore and avoid — especially for those outside the bubble of activity.

This blog post will look at some of the challenges of climate change communication, which provide both caution and motivation for after the crowds disperse.

One topic of recent conversation is the mental toll of climate change, which links with why it’s such an easy (and tempting) issue for people to ignore. The reasons that climate change is so difficult to grasp, psychologically, are outlined here and here.

To try to overcome these psychological barriers, climate change communicators have adopted common approaches to communicating climate change: focusing on solutions, using stories, and ‘framing’ the issue (that is, selecting and emphasising certain information and messages depending on the audience).

These strategies recognise the varied demographics within societies and the need to target information to make it more relevant to each audience. But there’s another layer of diversity to account for, too: the broader spectrum of public attitudes towards climate change.

Activists are only one segment of the public

In 2008, the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication conducted a nationally representative survey of Americans’ beliefs, behaviours and policy preferences relating to climate change. Their findings led to them classifying the American public as the ‘Six Americas’.

The ‘Six Americas’ represent six distinct groups into which Americans fall when it comes to their level of climate change engagement, spanning a spectrum from ‘Alarmed’ to ‘Dismissive’.

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

In their words:

- The Alarmed are fully convinced of the reality and seriousness of climate change and are already taking individual, consumer, and political action to address it. The Concerned are also convinced that global warming is happening and a serious problem, but have not yet engaged the issue personally.

- Three other Americas – the Cautious, the Disengaged, and the Doubtful – represent different stages of understanding and acceptance of the problem, and none are actively involved.

- The final America – the Dismissive are very sure it is not happening and are actively involved as opponents of a national effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

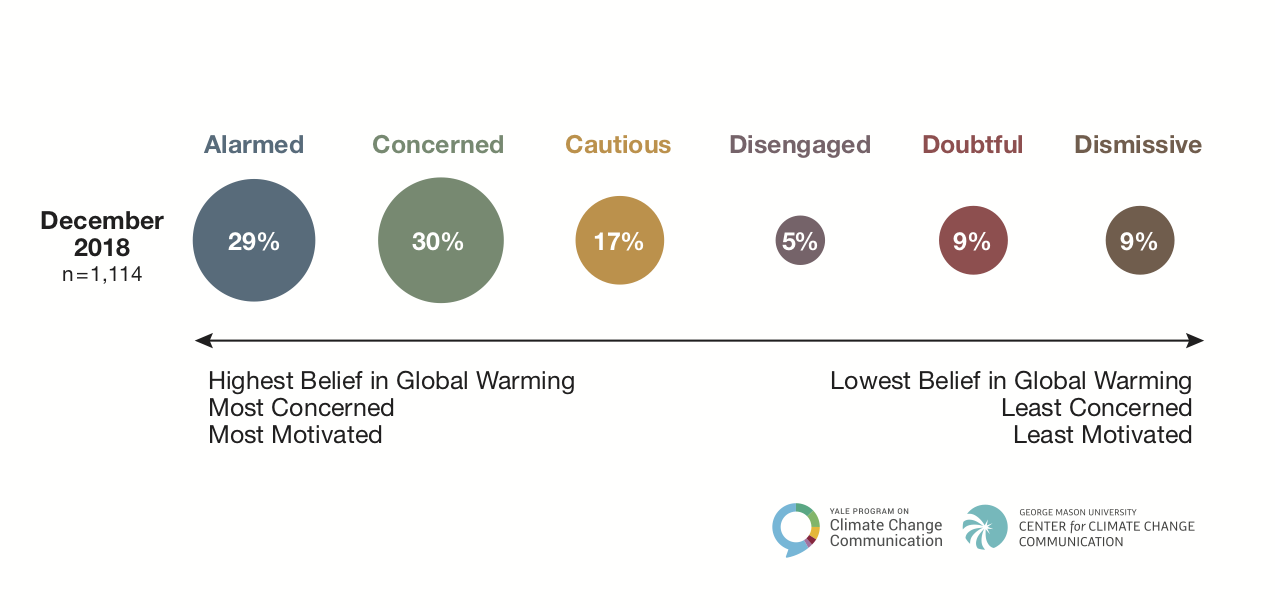

For the past 10 years, the authors have tracked the size of each group, using this framework to analyse the fluctuations of public attitudes over time.

Since 2013, the proportion of ‘Alarmed’ has more than doubled. Consistently, though, the majority of respondents are in the range of ‘Doubtful to ‘Concerned’, meaning that they are neither personally engaged nor actively involved with climate change as an issue. Their most recent survey was conducted in December 2018:

Source: Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

Although sourced from and applied solely to the American context, this spectrum provides a useful guide to the attitudes that underlie climate change action and inaction, even if the proportions will differ across countries.

At core, those strategies to overcome psychological barriers are all attempts to move disengaged people further along the spectrum, by opening them to the realisation of climate change, and increasing their motivation to act on climate change as an individual, as a consumer and/or as a voter. The climate strikes are a visible example of that shift for a sizeable number of the public. But overcoming the initial psychological barriers – which has happened for them, but not yet for others – is also only one step in what’s needed for sustainable behavioural change.

It’s a messy world out there

Shifting people’s attitudes on climate change, so that they are more engaged with it and motivated to act, is a precarious task. Any shift in perceptions must confront a messy, noisy world – the external challenges to climate change communication.

The field of climate change communication has evolved over time. As with science communication generally, it’s seen a move away from the ‘information deficit’ model; that is, the idea that public understanding can be improved and behaviour changed simply by providing (more) information. Today, there’s a much greater recognition of the role of context, personal values and psychology, which all mediate how people receive and process information. As such, attention has shifted to the ‘framing’ of information.

But the basic issue of inadequate or incomplete information shouldn’t be overlooked. At times of crisis, people look for and demand information. This is the case both in and outside the climate change context – for example, Google searches for ‘climate change’, ‘global warming’ and related terms spike at times of extreme or unusual weather.

The reality? It’s extremely hard for time-poor non-experts to find accessible and easily digestible information on climate change online, and to filter out misinformation.

While the communication of climate science has improved greatly over the years – not least because of the dedicated efforts of climate scientists themselves, including Ken Caldeira, Katharine Hayhoe, James Hansen, Michael E. Mann and Gavin Schmidt – public understanding and engagement remain vulnerable to credibility wars, cross-disciplinary noise, and to short-term media and political cycles.

History warns against complacency. The need for climate action has energised widespread public, media and (to an extent) political attention before. In 2007, following the release of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth and its Academy Award win, public interest and concern about climate change were at an all-time high. That same year saw the Nobel Peace Prize jointly awarded to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and Al Gore; the start of the now-global annual campaign ‘Earth Hour’, in which homes and businesses switch their lights off for an hour to symbolise mass support for climate action; and Kevin Rudd elected as Australian Prime Minister on a platform to address climate change as the “great moral challenge of our generation”. In 2008, Barack Obama became US President after an election campaign in which he pledged action on climate change.

In hindsight, this period marked a peak in public engagement with climate change, which was capped by the failure of the 2009 UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen to produce meaningful commitments. Since that peak, public opinion has been buffeted by increased political and ideological polarisation and controversies (such as ‘Climategate’, the 2009 controversy about emails hacked from the University of East Anglia’s Climate Research Unit, which was ultimately found to be baseless but led to a decline in public belief in climate change and trust in climate science in the US).

Meanwhile, a wealth of knowledge exists on climate change of which the public is simply unaware, which if known could help to increase or fortify the engagement of the vast number who don’t fall within the extremes of the spectrum.

This is a symptom of two wider issues:

- The public doesn’t have (and never has had) the full breadth of information on climate change, because the vast majority of information is contained in silos within disciplines and groups, and fragmented across sources; and

- Most information isn’t easily accessible or understandable by non-experts (that is, those outside the silos and groups), and to the extent it is, it provides an incomplete picture because – following the now-dominant approach to climate change communications – it’s generally ‘framed’ in a certain way (for example, for environmentalists or activists).

These silos are historical and structural. As Part 3 of this series will explore, as the ultimate public and cross-disciplinary challenge, climate change has the ultimate translation problem: the languages that are used to analyse it are technical (academic), discipline-specific, and, without conscious effort, do little to engage the mainstream. Because of this, people don’t use a common language to communicate and debate climate change – and this makes public understanding particularly vulnerable to uncertainty and doubt.