My White Blood Cell Count is Low (Biodiversity Loss)

Bluey’s been feeling blue. So, on the advice of the doctor, he’s taken it upon himself to visit nine specialists—all experts in their respective ‘planetary-boundaries’. Bluey wants to find out exactly what’s going on.

For more context generally and a description of why we’re doing this series, check out ‘My Climate Change Metaphors‘.

____

Hi guys, Bluey here again.

Today’s appointment shouldn’t have come as such a surprise, but it did. Firstly, I’d completely forgotten the unforgettable fact that over 99.9% of my white-blood-cell species had already gone extinct. Secondly, I’d had the fortune of meeting Dr Barnosky et al previously, though had seemingly forgotten that as well! Lastly, and most perplexingly, directly following our appointment, I found myself wandering aimlessly inside London’s Natural History Museum, staring up at ‘Hope’, their new Blue Whale centrepiece. I don’t normally get that soppy about my inhabitants.

Hope in all her glory (Credit: NHM)

Dr Barnosky, an acclaimed academic and author in his spare time, talked me through my medical records for half an hour, citing five periods of low white-blood-cell counts (or ‘mass-extinctions’ as he liked to call them). FYI, that’s when over 75% of my estimated surface species were lost forever. In chronological order, they were my:

1) Ordovician: ~443 million years ago

2) Late Devonian: ~359 Mya

3) Permian: ~251 Mya (when my white blood cell count was lowest)

4) Triassic: ~200 Mya

5) Cretaceous: ~66 Mya (when my Tyrannosaurus and Diplodocus white blood cells disappeared forever).

Out of the five of them, I recalled the ‘Cretaceous golf ball incident‘ best, and not just because it was the most recent. At the time, I couldn’t kick the following thought for years: how could something so small manage to cause such wide-ranging and long-standing consequences? After all, the ball had only hit my ‘Yucatan peninsula’ near my chin. Yet somehow, my whole surface went into an extended state of light-deprived asphyxiation, supposedly caused by the impact’s attendant release of bodily dust and debris into my atmosphere.

The other four low-white-blood-cell-count events were hazier, but I knew about them at the time; that much I could remember.

Whilst Dr Barnosky processed my results, I struck up a conversation with his assistant Nurse Hooper et al about the effects of plant species loss on my ‘ecosystem services’. Despite coming from a distinctly human perspective, he brought the relevance of species loss on other vital processes like primary production to the fore.

I also learnt from Nurse Hooper that species loss would have to be in excess of 75% before rivalling other environmental changes like nutrient pollution and drought. I was optimistic. But not for long.

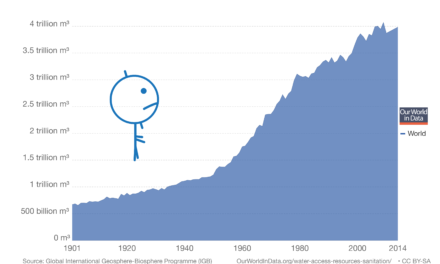

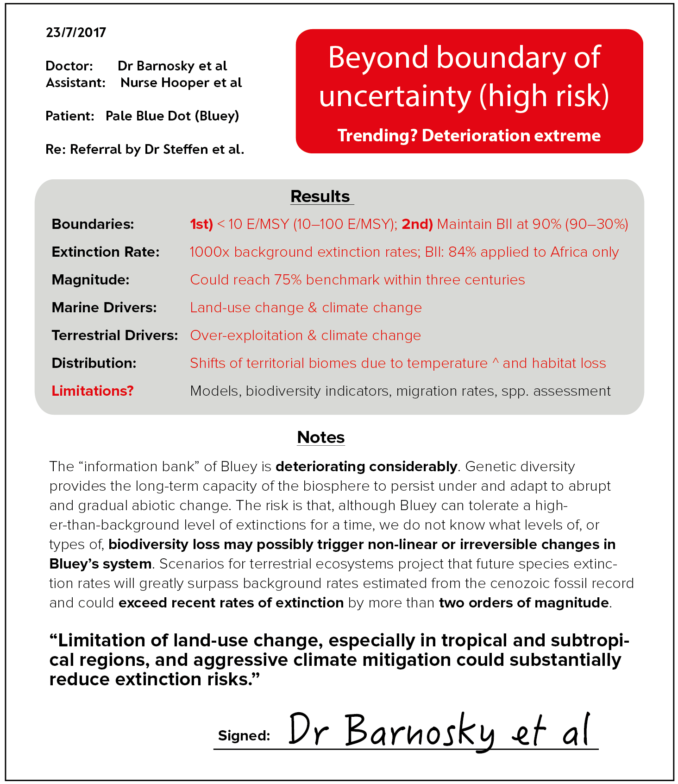

Medical Report Card 3 – Biodiversity Loss

- E/MSY: Extinctions per million species-years

- BII: Biodiversity Intactness Index (this is too complicated to explain here but more details can be found with Dr Scholes)

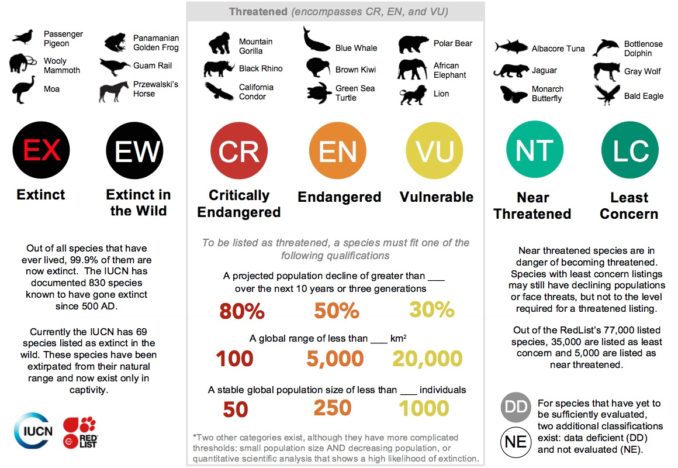

At a glance, it looks like I’m going to have to rely on humans again… If they’re listening, their priority has to be in protecting all my threatened species—and not just what they consider ‘charismatic invertebrates’—otherwise I could very well suffer my sixth great extinction event in the space of just a few more years.

IUCN RedList (Source: IUCN)

Surely the potential self-inflicted consequences will wake them up soon enough? At the very minimum, I know one thing for sure: they’re odds on to go down in my medical records as the cause of the Anthropocene’s equivalent to my ‘Cretaceous golf ball incident’.

While Dr Barnosky and his assistant’s meta-analyses were unequivocal, I couldn’t help but notice some of the ‘limitations’ on the medical report. As soon as I’d returned home, thinking it only prudent to collate a selection of ‘second’ opinions, I organised a conference call with Dr Thomas, Dr Vellend, Dr Brook and Dr Seddon.

Light on data, heavy on opinion, Dr Thomas explained how humans could be boosting my biodiversity by encouraging the hybridisation of species and ‘indirectly’ increasing temperatures, stressing that ‘new’—as opposed to traditional—species shouldn’t be stigmatised. In my humble opinion, Dr Thomas raised important points, especially that empirical data must lead the way, not irrationality, however I believe he failed his own test here.

On the other hand, Dr Vellend came equipped with a data-rich rebuttal of Nurse Hooper—around the importance of biodiversity as an ‘ecosystem service’. From Dr Vellend’s perspective, previous studies had rested on “untested assumptions”. There was in fact, no significant empirical change in net local-scale plant biodiversity over time. But because of his local focus, I chose to ignore him. That was until I heard Dr Brook’s opinion.

Dr Brook presented me with the best news of the day. Despite the potential loss of global species biodiversity, my functioning and resilience would likely remain strong. He described the functioning of my biosphere ‘health’ as the “aggregate contribution of the many component ecosystems operating on local and regional scales”. So local does matter! I even learnt at a regional scale, there’s sometimes a net increase in species diversity, such as on oceanic islands, in spite of species richness becoming more “globally homogenised” generally. Promising.

Dr Seddon offered neutral but informative thoughts around human conservation efforts. The translocation of species, assisted colonisation, ecological replacements and ‘rewilding’ all come with the best of human intentions, but with mixed results in practice. I think insisting that restoring species in a changing world requires “resetting public aspirations of biodiversity” was on point but should certainly not be used as another convenient excuse by humans.

Big Killers (Source: Nature)

There’s cause for worry and cause for hope. Most pressingly, humans must recognise the importance of biodiversity for their own sake because from where I’m standing, my white-blood-cell count may be decreasing, but I’m ultimately going to be fine. I’m just not so sure about everyone else.