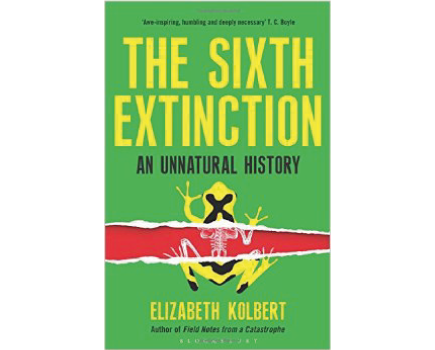

The Sixth Extinction

ELIZABETH KOLBERT

Very few of us ever feel compelled to really comprehend geological deep time. Why should we? In a few thousand years, a blink in the cosmos, we will be long decomposed and molecularly scattered. Earth will be here, but we won’t.

With The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, Elizabeth Kolbert joins the ranks of authors Bill Bryson, Richard Dawkins and Neil deGrasse Tyson—also presenter of the TV documentary series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—who understand the merits of appreciating deep time. And as authors, they can expertly communicate that to us, or at least try. Their main weapon of choice: analogy, one of the few techniques that can reveal to us what is otherwise invisible.

In The Sixth Extinction, Kolbert uses a different but equally powerful technique. She begins by asking us to imagine a new species that emerged around 200,000 years ago faced with what you’d expect one to encounter: hostility, competition and above all, a necessity to adapt. Soon this species—thanks to a few unique traits such as intelligence, curiosity, language and cooperative behaviour—manages to reproduce and spread itself expediently across the earth’s surface. Its members even find ways to cross oceans without having to evolve back into amphibians. Eventually, this resourceful biped manages to transform 70 per cent of the planet’s surface, extract its subterranean energy reserves, and enslave or extinguish many of Earth’s other occupants for its own benefit.

Hearing yourself spoken about in the third-person can be disconcerting or it can be ego-boosting. Hearing your own species spoken about in the third-person can be both as well, but here it’s firmly the former. Each chapter loosely bases itself on an animal species that has been driven off the planet, mostly by us. It’s not all turmoil though. Within the chapters chronicling the plight of Panamanian frogs, ancient ammonites and struggling Sumatran rhinos, there are entertaining tangents into history and science, usually both.

Extinctions are rare—very rare we learn—but we’ve managed to normalise the idea ever since ‘extinction’ was theorised and empirically proven back at the dawn of the 19th century by French naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier. In the years that followed Cuvier’s discoveries of Mastodons, Pterodactyles and giant Amphibians, numberless other ‘worlds previous to ours’ began emerging from beneath us. Emerging alongside these fossils was a new scientific discipline and a persistent question: what exactly had caused their demise?

There have been five major extinctions in the last half-billion years, two of which you may be vaguely familiar with. One is the demise of the dinosaurs (the Cretaceous extinction) 66 million years ago—most likely from a meteor impact on what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. The other is the mother of them all: the end-Permian extinction. This event—252 million years ago—eliminated 90 per cent of all species on the planet. Its likely cause: a change in the climate driven by an enormous release of CO2.

A more recent episode began a little over 10,000 years ago. Speculation ran rife as to the exact cause of the Megafauna extinction, but now there is little doubt about what killed off the mastodons, the mammoths and the giant marsupials. Many large animals didn’t have the good fortune to co-evolve with humans (as some did in Africa), and therefore learn to avoid them. Even those that did could be undone quickly as the tools and populations of humans increased voraciously at the end of the last ice age.

New Zealanders have their very own example: another ‘M’, the Moa, flightless and thus defenceless against their indigenous settlers. Even their other great bird the Haast’s eagle—the one that could fly—couldn’t repel the onslaught and died out in about 1400A.D.

Strikingly, throughout the book Kolbert resists placing intent or blame on her species for the past or even the now. She acknowledges that we’re just unwittingly doing what we’ve always been good at—outcompeting everything else. But that, of course, is no excuse in Kolbert’s books. Intent is one thing, awareness another. We now know exactly what we’re doing.

Seeing through the gloom that hovers over each and every chapter is easier than you’d think though with Kolbert at the helm. An investigative journalist for the New Yorker, Kolbert is most at home when weaving personal and biographical stories into her otherwise depressing revelations. Personal anecdotes from the Amazon to the Great Barrier Reef provide vividness and, at certain junctures, timely specks of optimism.

But above all, Kolbert gets you to reflect and foresee. Whether you agree with her tone will depend much on your own ideology, but the specifics are hard to deny and impossible to ignore. Her well-researched science and accessible writing make for an informed exposé of extinction as well as planetary existence in general. The book armed me with a better knowledge of ocean acidification and climate change, the two inter-related threats we all have a responsibility to understand. And the geek inside me recognised terms forgotten from school: the Mesozoic, Cenozoic, Triassic, and a new one: the Anthropocene.

To communicate how insignificant our time on this planet has been, Dawkins used the pages of books and nail clippings, Bryson skyscrapers and half-inches, Tyson a single day with its hours, minutes and (particularly) its seconds. Kolbert does the same, but with The Sixth Extinction she smacks you in the face with just how significant that insignificance is. In a few thousand years we won’t necessarily be here, but our legacy will.

Kolbert articulates here how the start will read. What of the end?