Winning Quickly: Global Leadership on a Domestic Scale

Climate change means many different things to many people. So as you’ll appreciate, summing it up in just one simple phrase has defied communication specialists for quite some time. Despite this challenge, someone had a crack last year and actually came quite close. When it comes to climate change:

“Winning slowly is the same as losing”

In his 2017 Rolling Stone article, Bill McKibben reminded us all that while the technology exists globally to tackle climate change, there’s still those all important missing ingredients of urgency and action. “What exactly”, he asked, “will it take to get our leaders to act?”

Source: Hiretorque

King CONG is leaving New Zealand (coming soon)

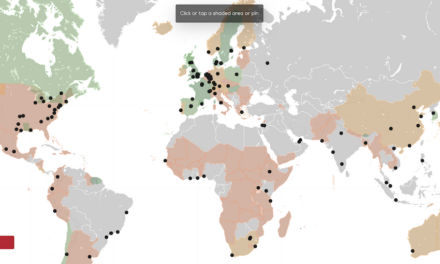

Last week, New Zealand (NZ) declared it will not grant any new permits for offshore oil or gas exploration. In doing so, it joined a small club of outlier countries that have taken a similar stand, including France, Costa Rica and Belize. Like those countries, NZ is pathetically small in the context of the King CONG world of Coal, Oil and Natural Gas. The industry makes up only 1.4% of NZ’s economy making the decision politically possible, but as expected, an exasperated opposition was triggered around how the decision will negatively affect jobs and the economy.

While unlikely to be reassuring, a few bones of short-term “certainty” were thrown out to workers and advocates within the industry. For example, all 22 existing off-shore exploration permits are protected under the policy change (the last of which elapses in 2030), and in theory, all existing permits could be renewed under a mining permit for a further 40 years. In short, there are some caveats.

Nonetheless, those in political opposition have brandished it variously as:

- Economic vandalism;

- A wrecking ball through regional New Zealand [that] doesn’t make environmental sense; and

- An appalling decision… their current leader lacks the experience to understand the issues.

Let’s address these, in reverse order.

1. New Zealand’s leader doesn’t understand the issues

This kind of depends on if we look at the issues through global or domestic glasses. Whether or not we reach for our long-term lens instead of our default short-term lens is also relevant.

I’ll say it again. Climate change is our world’s biggest issue, on par with the old, persistent one of nuclear proliferation, and the new, mysterious one of tech disruption (I’m talking Artificial Intelligence gone wrong or Cyber warfare). Here’s the crux though: climate change actually makes the latter two more likely because it’s a “threat multiplier”, whereby a future nuclear exchange becomes all the more probable as climate change speeds up. More explicitly, a warming planet will heat up tensions on the most volatile parts of our planet — a prospect that will make the powder keg bigger when conflict over resources eventually sparks. In fact, there are those (here, here and here) who estimate it already has. Others don’t want to overstate it.

You might be thinking, hold your horses, political pony NZ only contributes a puny proportion to the most powerful industry in human history, so, why should it matter what they do? Or maybe you’re thinking about the little guy, or less likely, the tax man: why would it turn its back on an industry that could deliver jobs long into the future and bring revenue into its coffers? The answers are simple but that’s because they’re unapologetically global. They have to be.

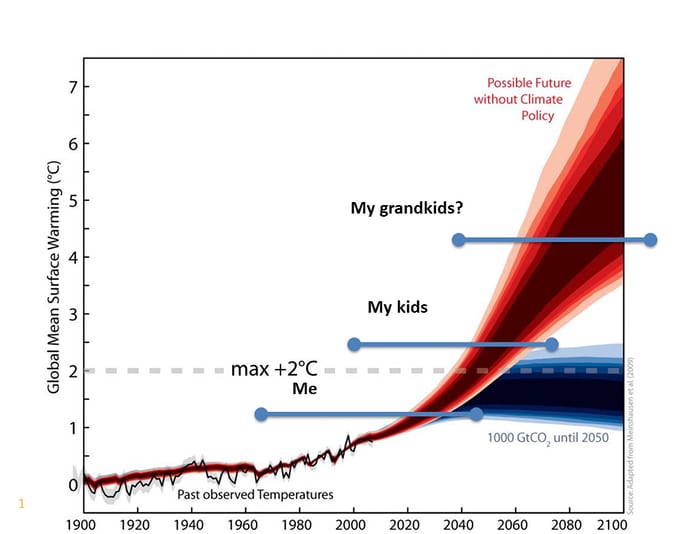

Unactioned climate policy vs Actioned climate policy (Source: The Guardian)

Firstly, small is still symbolic. Russel Norman, executive director of Greenpeace NZ, spelt it out in a quote for the Financial Times:

“Just as New Zealand did in 1987 when it went nuclear-free and stood up to the powerful US military, this has shown bold global leadership on the greatest challenge of our time — putting people ahead of the interests of oil corporations and the hunt for fossil fuels that are driving dangerous climate change”.

Put another way, speaking up when no one else is willing to is a luxury NZ can afford, politically and fiscally. New Zealand is in the deeply privileged position where they can see the world tomorrow and act on that world today. Rephrasing the famous Edmund Burke quote:

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of [human-induced climate change over humans] is for good men [and women] to do nothing.”

Secondly, “unless we [think NZ and humanity] make decisions today that essentially take effect in 30 or more years time, we run the risk of acting too late”. The Prime Minister of NZ, Jacinda Ardern, was right but she was also wrong. To have minimised that risk sufficiently, infrastructure decisions that take the global economic trajectory completely off the fossil-fuel highway should’ve been made more than 10 years ago. Nevertheless, just because it might already be too late doesn’t mean the next best time to start isn’t today. That’d be like saying I’m not going to bed now because I wasn’t in bed earlier.

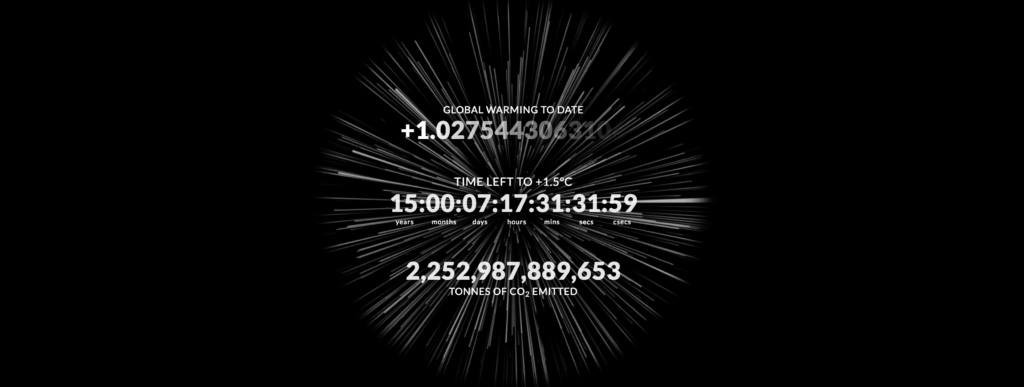

Climate Clock (Source: Climate Clock)

Or think of it another way: New Zealand, by 2030, will be in the peloton on the only viable route that doesn’t go off the cliff on the Tour de Humanity. Even though they’ll be in the lead group, they’ll look pointlessly feeble and politically weak to start off with, but eventually they’ll get a big, brave name to join them. And then they’ll have the guy in the yellow jersey join them. The rest will follow slowly, but after a few decades, they’ll all come. Because they have to.

Climate scientists the world over assure me as I conduct my research: there is a vast difference between a world that stabilises at two-degrees and one that stabilises at three or — Trump willing — four degrees warmer than our pre-industrial average. As the World Bank and Royal Society warned us separately a few years ago, at four degrees above our pre-industrial level:

“Limits to human adaptation are likely to be exceeded in many parts of the world, while the limits for adaptation for natural systems would largely be exceeded throughout the world.”

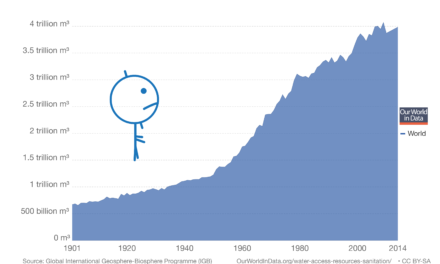

As dystopian as that sounds, if we don’t start turning the emissions tap off really fucking soon, four degrees is what’s probably going to happen. Read about the maths of climate change here, or take a look at the geeky (but great) Katharine Hayhoe video below to find out how at current rates of emissions, we only have about 25 years of ‘carbon budget’ left.

Ok, so what about the Paris Agreement — that thing that’s supposed to save us from ourselves? That brings me to the third and most vital part of understanding this issue.

The Financial Times noted:

“The South Pacific nation’s ban is an important policy move at a time when nations are exploring how to comply with their requirements under the Paris climate change agreement”.

In 2018, as the international community readies itself to take Paris seriously, complying with Paris’s emission-cutting expectations to “ratchet up” global targets will be no cake walk — in fact, it could be the hardest thing the international community ever does. A big chair does not make a King.

Paris’s reason for being is to keep global average temperatures “well below” an increase of 2.0°C by the end of this century (as compared with our pre-industrial average). To have between about a 5% and 67% chance of even doing that, it’s agreed we have to:

“Achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty.”

In other words we have to get to zero emissions, but at the same time, try not to lose sight of other responsibilities — especially to those who are least responsible for causing the problem. Some think about it in terms of a “Just Transition” — a euphemism for moving quicker than we ever have before and not losing sight of our least well-off.

For NZ, the moving-quicker-than-we-ever-have part is going to be hard. The latest data shows its emissions were down 2.4% from 2016 to 2017, but still 19.6% higher than in 1990. Achieving Paris’s lofty targets — and NZ’s own goal to reduce GHGs by 30% below 2005 levels by 2030 — is going to take a lot more than banning oil and gas permits. But it’s a signal, and it’s a start.

2. Banning exploration permits is “a wrecking ball through regional NZ [that] doesn’t make environmental sense”

Regional areas in NZ are unhappy, but then when decisions are made under utilitarian and future-proofing principles, that’s a given. Hard political decisions upset.

But hard decisions also provide long-term certainty to people, their job creators (businesses) and investors.

The direction of travel is becoming unambiguous the world over, and while many locals saw this particular domestic decision as too abrupt and non-consultative, bad process should not cloud good substance.

That is to say, existing permits remain and current jobs are secure for the next decade; but simultaneously, the 11,000 people directly and indirectly involved have had their expectations managed. That sounds perversely insensitive, but it’s wholly necessary given the context. And besides, all change entails stages of grief — packaged often as denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. The quicker New Zealanders involved in this industry become desensitised to the inevitability of change and exit this grief process, the better.

First-mover advantage

Moving early on this will also push NZ onto the path of a transition to 100% renewable electricity, maybe before 2040. In itself, that will open up economic opportunities. It will also stimulate substantial investment in renewables which the international market is already embracing with giddy alacrity: 157 gigawatts (a lot) of renewable energy capacity was commissioned last year versus just 70 gigawatts of fossil-fuel capacity.

Solar and Wind (Source: Climate Visuals)

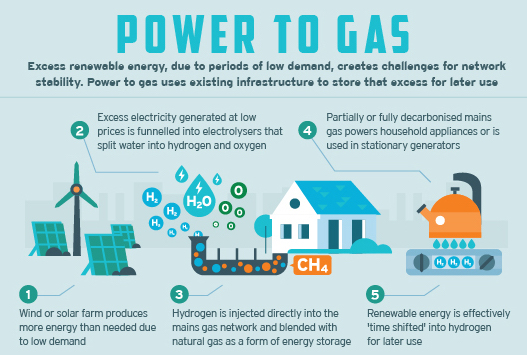

Another not-often-enough cited trend is that coal power is already becoming uneconomic in many countries, as pointed out repeatedly by coal and gas expert, Matt Gray, of Carbon Tracker. For Gray, the prospect of countries like NZ exploring future transition technologies gets him excited. He told me about one example, ‘Power-to-gas’, which allows intermittent renewable energy (wind and solar) to be ‘stored’ for later use (by splitting water into Hydrogen and Oxygen, and then adding CO2 to generate Methane — the main part of natural gas). Deployed in a country like NZ, such a technology might even allow it to keep existing gas infrastructure and most of the value chain associated with that infrastructure. Matt says Germany is already investing in it.

Power-to-gas (Source: ARENA)

The above is one possible example of how a future NZ could play out, but what’s certain, is once acceptance takes hold, it’s going to be an exciting time for regional areas as the next decades’ sunrise industries emerge. And ahead of the chasing pack.

3. Banning exploration permits is “economic vandalism”?

This inflammatory statement is as patently wrong as it is harmful. Max Harris, a rising public intellectual, put it well recently: “there isn’t a simple trade-off between the economy and the environment when it comes to climate change”.

Long has it been hammered home by economists: acting now (that ‘now’ being a decade ago) will save us billions, likely trillions of dollars. Nicolas Stern’s 2006 report is still the most widely referenced source, but there are many, many others who agree with him. To refresh our collective memory, the UK government-commissioned ‘Stern Report’ concluded:

Strong, early action considerably outweighed the costs of inaction

Unabated climate change could cost the world at least 5% of GDP each year; if more dramatic predictions come to pass, the cost could be more than 20% of GDP

What we do now can have only a limited effect on the climate over the next 40 or 50 years, but what we do in the next 10-20 years can have a profound effect on the climate in the second half of this century

Shifting the world onto a low-carbon path could eventually benefit the economy by $2.5 trillion a year.

Organisations such as Mission2020, the C40 initiative, Action2020 — alongside individuals such as Christiana Figueres and Johan Rockström — have this urgency in their DNA but are at constant pains to wake the rest of us up from our collective economic and environmental myopia.

In the NZ context, a joint effort between Ernst Young, Vivid Economics, and Westpac Bank spat out a report stating:

“The sooner NZ acts, the cheaper it will be. The economy is projected to be $30 billion better off if we start now rather than in 2030”.

The delayed and asymmetric impacts of climate change necessitates incredible urgency. What the world decides today matters far more than what it decides in 2020, and exponentially more than what it decides in 2035. To give our civilisation time to adapt but also to save us all an enormous amount of money.

Sometimes it doesn’t take balls

It’s an unavoidable cliche but big long-term decisions take bold leadership that upsets some in the name of what’s right, and in this case, what’s economically right. In “setting [people’s] expectations for the future”, NZ’s leader has put her country up as an example of what has to be done by every other nation in the world.

Winning quickly demands that others also start thinking global, looking long and acting now.

Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand’s Prime Minister and Leader