We’ve Been Institutionalized By Technology

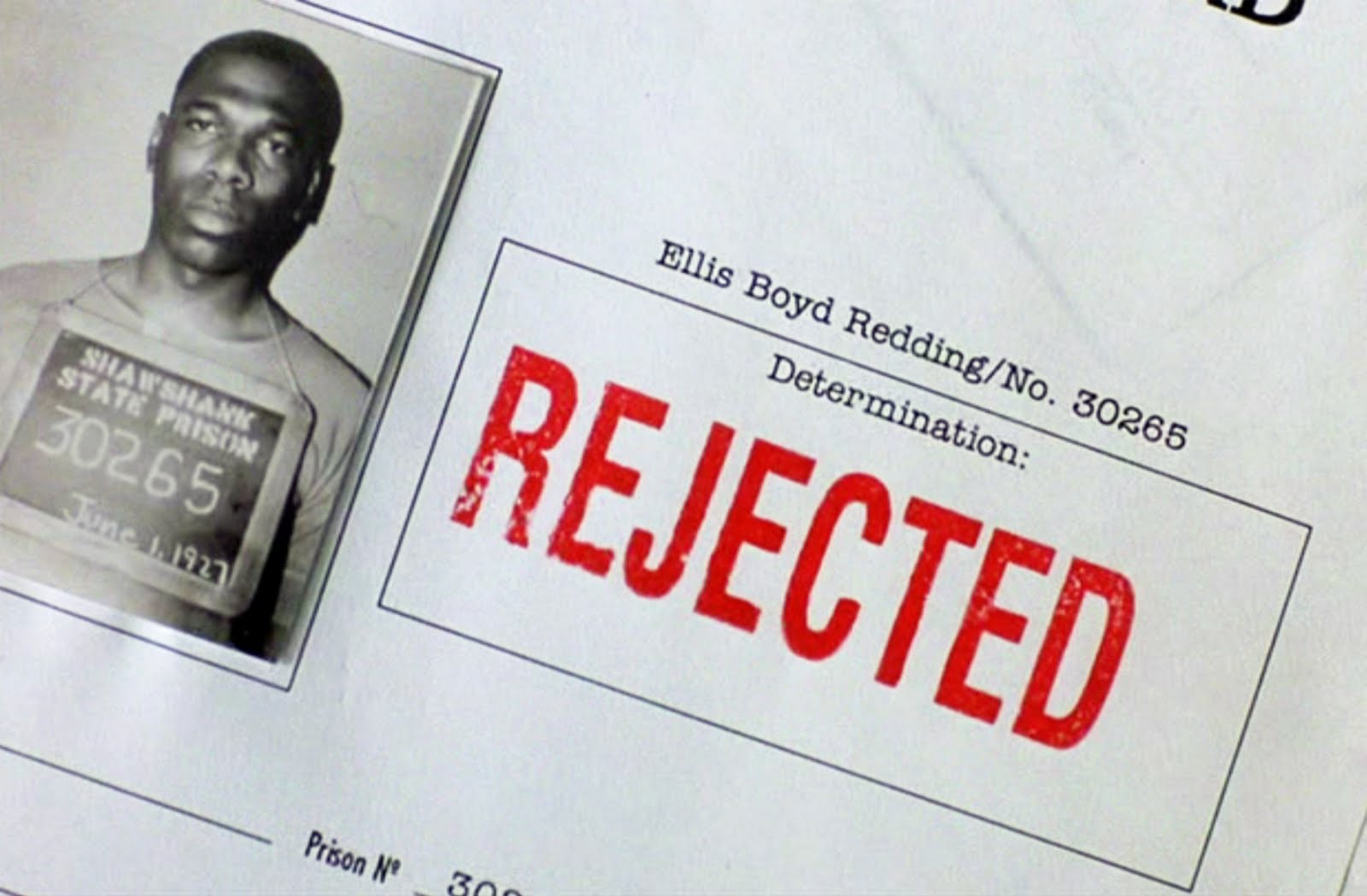

Who doesn’t love The Shawshank Redemption? I’ve only seen it a gazillion times. There’s so many endearing elements to it: the camaraderie amongst the prisoners, the melancholic score, and [spoiler warning] the thrill of Andy Dufresne’s escape [end spoiler]. But what sticks out the most is a line from Morgan Freeman’s character – Red, about the ‘institutionalization’ of prison life:

These walls are funny. First you hate ’em, then you get used to ’em. Enough time passes, you get so you depend on them. That’s institutionalized.

Sure, anything Red says is memorable – Freeman has velvety pipes. But in admitting there is psychological comfort in certainty and routine, he speaks universally – to those without a record. Because you don’t have to spend time in prison to become imprisoned by something, or have a sentence to do time. Many of us serve time – to our screens, where we’re held captive for many hours of the day. That’s tech-institutionalized.

Credit: Action Press / Rex / Shuttershock

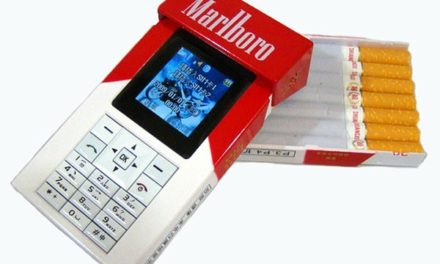

The digital dependency

I’ll be the first to admit I’m tech-institutionalized: I’m frequently on my phone getting a screen tan. But it’s not all mindless scrolling or Clash of the Titans – I source my news from Twitter, scribe notes on Evernote and get around via Google Maps. These apps have become essential to my day-to-day, augmenting my memory and keeping me in the loop. And on the odd day I’m without my little digital companion, I feel toothless, like a boy scout without his swiss army knife.

My digital dependency goes deeper. I rely on my phone to socialise, choosing to break bread in byte sizes. WhatsApp and Snapchat are my social networks of choice, each offering communion by convenience, a virtual dinner table to gossip and share stories. And while I’m aware FaceTime isn’t actual face-time, I need it for my nasal-gazing rants across time-zones. Though I could do without the double-chinned monster that greets me each time I turn on the front-facing camera.

This isn’t a mental asylum

So yes, I’m tech-institutionalized, but for good reason. My connection to my phone is a legitimate dependency, come about from offloading my social life and dozens of administrative tasks that demand frequent attention and reciprocation. And while it may stray into an unhealthy habit from time to time, integrating my phone into my life is for the most part, transformative. But this doesn’t make it any less of a dependency.

Many of the tech naysayers will tell you different. To them, this is an addiction, and being tech-institutionalized is akin to being admitted to a mental asylum. They would say it’s an illegitimate dependency, like a gambling habit or a nervous twitch – something to treat and fix. So, they preach digital detoxes and for people to reign in their tech use. It’s admirable, but they largely miss the point.

The reality is many cannot crudely disconnect from their digital devices. Some folk use their phones to check on their kids or elderly parents, while others have jobs requiring them to be easily contactable. Asking them to stop using tech is like asking the mayor to switch off the electricity grid: it’s cutting off their life support. Even getting off Facebook is tricky. The world’s most popular social network is today’s equivalent of the white pages – the place to find contacts and rally friends. Sure, the news feed may be more yellow pages than white, but to be off Facebook is to risk social exclusion.

Don’t forget about the guards

There is a significant downside to being tech-institutionalized. We’re not alone. Our guards – Facebook, Google etc., are watching and tracing each of our steps: what we share, search for and the places we visit. Under their eternal gaze, we become happy prisoners under house arrest, wearing our location sensitive monitors – not on our ankles, but in our pockets and on our wrists. And while we have the freedom to go where we choose, our free will is systematically being hacked. Notifications are coloured red, and news feeds turned bottomless. This is all deliberate to keep us scrolling and our eyeballs glued to the screen.

This is the danger of being tech-institutionalized. It’s a for-profit prison, where your own interests don’t come first. As the big money lies with collecting data, many of the services are designed to yield as much as possible. The effect is quite perverse: instead of Facebook promising to merely connect us, their real goal is to connect us all the time. This is why it’s so tricky to stay on top of the privacy settings or work out how to delete your account. Like Red and his experience of parole in The Shawshank Redemption, the system feels rigged, because they don’t want us to leave.

Restorative tech justice

What we need is a restorative justice movement for tech. Where we don’t pathologize use, but instead think about the best way to administer the service. By tweaking the system that commodifies our attention, maybe we can break the cycle of relentless phone checking. Because unlike The Shawshank Redemption, there’s no Pacific Ocean for us to escape to, no tranquil place to live out the rest of our days. This is it. So bigger and philosophical questions need to be asked. Are services like social networking and information search in effect public goods? If we spend so much time on them should we expect higher standards of digital living? Should apps be accredited and have warrants of fitness?

The Shawshank Redemption brings to attention the issue of institutionalization, but it doesn’t give us the answer. In its final chapter, the recently paroled Red travels to Maine to track down his friend Andy Dufresne. He’s following some ambiguous instructions left behind by Andy: a box hidden at the end of a stone wall in a hayfield, in Buxton. They are the sort of directions that no one today would have ever found without the aid of Google Maps. Our institutionalization is permanent, a break out unrealistic. What we need is a jailbreak of the system.